Ko wai ngā rangatira i waitohu i He Whakaputanga?

Who were the rangatira who signed He Whakaputanga?

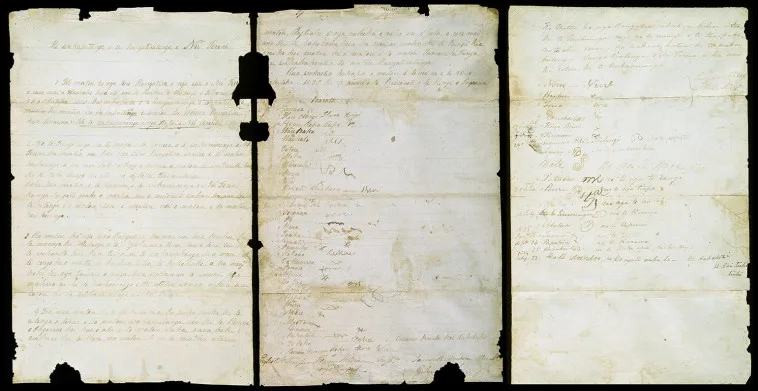

He Whakaputanga o te Rangatiratanga o Nu Tireni - known in English as the Declaration of Independence of the United Tribes of New Zealand – Recognised by the United Kingdom, signalled the emergence of Māori authority on the world stage.

He Whakaputanga o te Rangatiratanga o Nu Tireni – known in English as the Declaration of Independence of the United Tribes of New Zealand – is a constitutional document of historical and cultural significance.

Described by British Resident James Busby as the "Magna Carta of New Zealand Independence", He Whakaputanga was a bold and innovative declaration of Indigenous power. As Aroha Harris notes, He Whakaputanga was “an unequivocal statement of rangatiratanga by a people confident enough in their authority, ideas, and aspirations to debate their concerns in a period of rapid change.” Recognised by the United Kingdom, it signalled the emergence of Māori authority on the world stage.

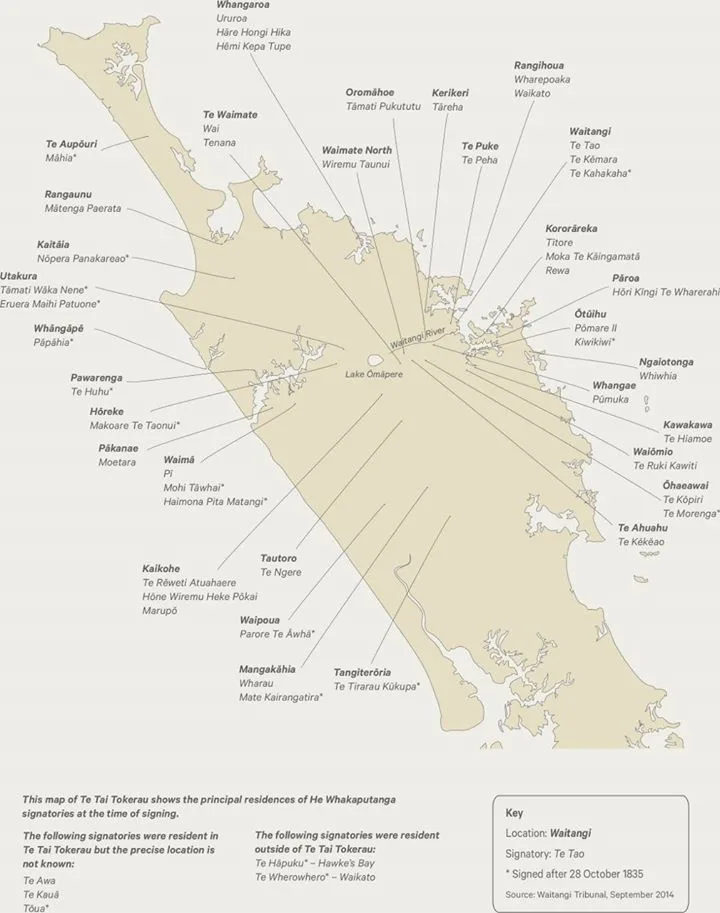

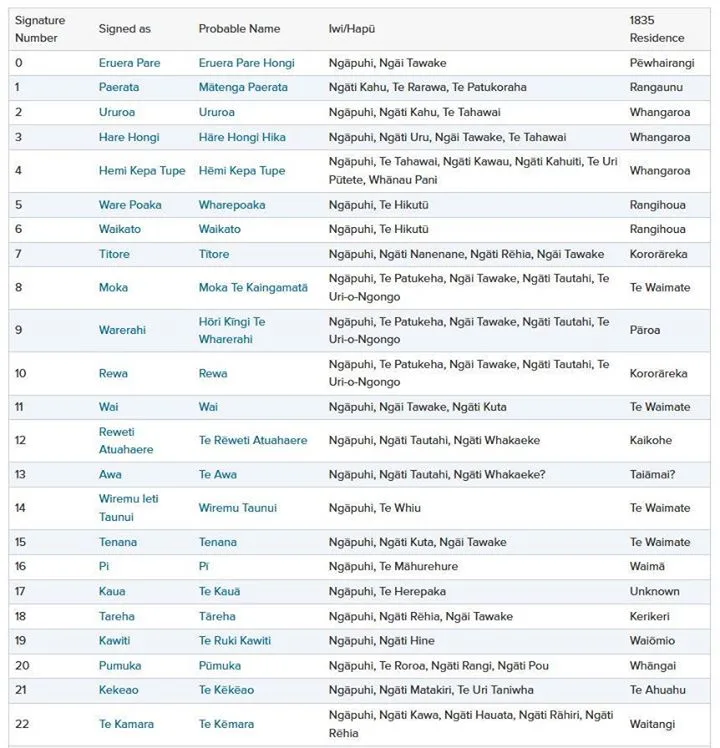

He Whakaputanga was first signed by 34 northern Māori rangatira (chiefs) on 28 October 1835. By July 1839, He Whakaputanga had collected a further 18 signatures. Through He Whakaputanga, these 52 rangatira asserted that Aotearoa New Zealand was an independent Māori state, that power resided fully with Māori, and that foreigners would not be allowed to make laws.

But who were these rangatira? And why did they sign?

Busby may have viewed the Declaration as a step towards making New Zealand a British possession. But Māori intentions were somewhat different. The rangatira who signed He Whakaputanga were continuing a tradition of safeguarding their people in the face of rapid change.

Northern Māori had been meeting in the Bay of Islands, Hokianga, Whangaroa, and Whāngārei as early as 1808 to work collectively and manage their relationships with Europeans. In contrast to Busby, the signatories saw He Whakaputanga as a way to address the challenges posed by European contact, to strengthen an alliance with Great Britain, and to assert their authority to the wider world. For Ngāpuhi, He Whakaputanga emerged out of the meetings of Te Whakaminenga, rather than Te Whakaminenga emerging from He Whakaputanga.

As Vincent O’Malley writes, all but two of the 52 signatories came from Northland. “They represented a diverse range of communities, including rival hapū and tribal alliances that had recently been at war with one another.” They include well-known names and also rangatira well-known within their own hapū but less-known to the wider world.

These rangatira owned ships, led war expeditions, provided for their people, traveled the world, met British monarchs, developed te reo Māori dictionaries, founded schools and churches, fought against the Crown, fought with the Crown, cultivated food, owned timber mills, wrote poetry, and much more.

The final two rangatira to sign extended the reach of He Whakaputanga considerably. Te Hāpuku of Ngāti Te Whatuiāpiti in Hawke’s Bay signed the agreement during a visit to the Bay of Islands in September 1838. Te Wherowhero (later known as Pōtatau Te Wherowhero), a leading Waikato–Tainui rangatira and future Māori King, also signed through his kaituhi (scribe), Kahawai.

As part of He Tohu and with the help of researchers and descendants, we undertook a significant amount of research to learn more about the rangatira who signed. The result was 53 short biographies, published in He Whakaputanga/The Declaration of Independence, 1835 by Bridget Williams Books, and as a He Whakaputanga Signatories database on NZHistory. The database is free to access online and includes the biographies of each rangatira.

Further research will continue to yield more biographical details, so the identification of those involved and the biographies represent ‘work in progress’. They are offered with a view to increasing knowledge of He Whakaputanga and its participants, and to encourage further research.

The biographies would not have been possible without the hard work of previous historians and researchers, the teams at BWB and NZHistory, and the generosity of descendants who shared their knowledge. Warm acknowledgement is also due to those of Ngāpuhi-nui-tonu who described their complex and illuminating histories before the Waitangi Tribunal.