Conservation of the He Tohu documents

The He Tohu exhibition space grew from the need for improved display and storage of these taonga after many years on display in our Constitution Room which no longer provided good storage or visitor experience.

Protection of significant centuries-old documents

How do you protect centuries-old documents, some of which had been chewed by rats in a damp basement many years ago?

This was the dilemma faced by conservators at Archives New Zealand and the National Library as they prepared some of our nation’s most important documents to go into the He Tohu exhibition at the National Library building on Molesworth Street, Wellington.

The He Tohu conservators researched the history of past storage, display and treatment, because conservation work is never done in isolation. Understanding past approaches, when previous conservators and archivists were charged with caring for these documents, helped inform decisions for He Tohu.

The documents, being Te Tiriti o Waitangi/The Treaty of Waitangi, He Whakaputanga o te Rangatiratanga o Nu Tireni/The Declaration of the Independence of the United Tribes of New Zealand, and Te Petihana Whakamana Pōti Wahine/The 1893 Women’s Suffrage Petition, were already fragile, so the team needed to think carefully about how to best move and display them in the new space. While the documents were only moving 250 metres from Archives New Zealand, it took a large team, months of planning and specially designed crates to make it happen.

The documents were moved respecting tikanga (cultural customs) and acknowledging the signatories, their descendants and staff who have cared for these documents.

-

![Archives NZ staff led by Ngā Toa/Valiant warriors bringing the documents into their new home.]() Click to expandArchives New Zealand staff lead by ngā toa/warriors bringing the documents into their new home.Photo by Mark Beatty

Click to expandArchives New Zealand staff lead by ngā toa/warriors bringing the documents into their new home.Photo by Mark Beatty![Archives NZ staff led by Ngā Toa/Valiant warriors bringing the documents into their new home.]() Click to expandArchives New Zealand staff lead by ngā toa/warriors bringing the documents into their new home.Photo by Mark Beatty

Click to expandArchives New Zealand staff lead by ngā toa/warriors bringing the documents into their new home.Photo by Mark Beatty -

![Crates with precious taonga inside]() Click to expandCrates with precious taonga insidePhoto by Mark Beatty

Click to expandCrates with precious taonga insidePhoto by Mark Beatty![Crates with precious taonga inside]() Click to expandCrates with precious taonga insidePhoto by Mark Beatty

Click to expandCrates with precious taonga insidePhoto by Mark Beatty

The team designing the new He Tohu exhibition faced the dilemma of how best to ensure a long-term stable preservation environment, particularly with the lighting.

These preservation concerns are why the document room is as it is today. It is a separate room – a ‘waka huia’ or treasure box of documents – where physical and cultural preservation measures are implemented with minimal impact on access. It has carefully controlled lighting, temperature and humidity, while the interactive and descriptive space have all the features that this exhibition deserves. The ‘waka huia’ also provides incredible strength to protect the display cases from hazards such as fire or earthquakes.

Other expertise ensured the cultural needs of the documents were met. Prior to construction, a whakawātea or ‘clearing the space’ was led by mana whenua to ensure the cultural needs of the documents were met.

Mauri stones sourced from places of significance were laid within the document room. The mauri, or life force, of He Tohu is concentrated in the stones, a living energy, a source of physical, spiritual and emotional wellbeing.

The He Tohu conservators collaborated for the design specifications of the display cases. Controlled humidity and lighting, and the ability to closely monitor the conditions within the cases, are features of their design.

Monitoring is how we manage the long-term conservation impacts of the exhibition and how we know we are providing the best conditions for these taonga.

-

![The whakawātea in the future Document Room/He Whakapapa kōrero space]() Click to expandThe whakawātea in the future He Whakapapa Kōrero/Document Room, led by Taranaki Whānui Te Ātiawa rangatira, Kura Moeahu.Photo by Mark Beatty.

Click to expandThe whakawātea in the future He Whakapapa Kōrero/Document Room, led by Taranaki Whānui Te Ātiawa rangatira, Kura Moeahu.Photo by Mark Beatty.![The whakawātea in the future Document Room/He Whakapapa kōrero space]() Click to expandThe whakawātea in the future He Whakapapa Kōrero/Document Room, led by Taranaki Whānui Te Ātiawa rangatira, Kura Moeahu.Photo by Mark Beatty.

Click to expandThe whakawātea in the future He Whakapapa Kōrero/Document Room, led by Taranaki Whānui Te Ātiawa rangatira, Kura Moeahu.Photo by Mark Beatty. -

![Mauri stones arrive at the National Library]() Click to expandThe mauri stones arrive at the National Library, carried by Haami Piripi (left) and Bernard Makoare (right). Raniera Tau of Ngāpuhi performs the karakia.Photo by Hinerangi Himiona.

Click to expandThe mauri stones arrive at the National Library, carried by Haami Piripi (left) and Bernard Makoare (right). Raniera Tau of Ngāpuhi performs the karakia.Photo by Hinerangi Himiona.![Mauri stones arrive at the National Library]() Click to expandThe mauri stones arrive at the National Library, carried by Haami Piripi (left) and Bernard Makoare (right). Raniera Tau of Ngāpuhi performs the karakia.Photo by Hinerangi Himiona.

Click to expandThe mauri stones arrive at the National Library, carried by Haami Piripi (left) and Bernard Makoare (right). Raniera Tau of Ngāpuhi performs the karakia.Photo by Hinerangi Himiona.

Lighting

Light exposure is the biggest challenge in managing the long-term preservation of the documents. Permanent fading, colour change or damage to the documents are real risks from inappropriate lighting. Our aim was to eliminate unnecessary light exposure and ensure the best quality light and viewing experience. This has been achieved by adjusting colour temperature and viewing positions and minimising glare.

-

![A woman with blonde hair bending and pointing towards a roll of paper.]() Click to expandChanging the pages on display of the Women’s Suffrage PetitionPhoto by TM Davidson

Click to expandChanging the pages on display of the Women’s Suffrage PetitionPhoto by TM Davidson![A woman with blonde hair bending and pointing towards a roll of paper.]() Click to expandChanging the pages on display of the Women’s Suffrage PetitionPhoto by TM Davidson

Click to expandChanging the pages on display of the Women’s Suffrage PetitionPhoto by TM Davidson -

![two women in a dark room, bending in front of a roll of paper with wooden circular wall behind]() Click to expandPetition change procedurePhoto by TM Davidson

Click to expandPetition change procedurePhoto by TM Davidson![two women in a dark room, bending in front of a roll of paper with wooden circular wall behind]() Click to expandPetition change procedurePhoto by TM Davidson

Click to expandPetition change procedurePhoto by TM Davidson

For example, we chose cool lights (a colour temperature close to 5000 degrees kelvin (K)) in the cases to give better contrast, which enabled us to lower the lux levels (the brightness). He Whakaputanga and Te Petihana could be displayed vertically, with hoods placed over the lights in most of the cases to reduce glare.

All the documents in the He Tohu exhibition have these strict lighting conditions. This is to protect the paper, parchment and inks from further light damage. Because Te Petihana has the most light-sensitive inks, we protect it in a special way. Four times each year, conservators roll the 546-page petition to change the pages on display. A record is kept of the pages that have been shown.

All the documents remain in the dark until the visitor presses the light button, to protect them from too much unnecessary light exposure.

The Archives New Zealand conservators track the number of times a light button is pressed, and the total exposure time is measured against the strict limitations in place. Quarterly graphs are produced showing the amount of light each document has received and whether it is above or below the amount allowed. Since the exhibition opened in May 2017 there has been no month when any light exposure has gone above the recommended limits.

By implementing these preservation measures, the documents can be on display safely for the full 25 years of the exhibition. In fact, the limitations that we have set are based on a continuing exhibition exposure for 500+ years, thereby ensuring the ability to have exhibitions in the future.

Temperature and Humidity

Paper and parchment documents are recommended to be stored in cool and dry conditions to preserve them for as long as possible. In He Tohu, the documents are all stored in climate-controlled display cases. The air is conditioned to the preferred relative humidity (RH) before it enters the case. The RH for most cases is around 45% and for Te Petihana it is around 50%.

The temperature in the cases is the same as the Whakapapa kōrero/document room, set at 19°C. This is a few degrees cooler than the rest of the exhibition space and the National Library ground floor.

-

![Bright rea color broken seal on a yellowed old sheet]() Click to expandSeal on the parchment Waitangi sheet, 55 x magnification

Click to expandSeal on the parchment Waitangi sheet, 55 x magnification![Bright rea color broken seal on a yellowed old sheet]() Click to expandSeal on the parchment Waitangi sheet, 55 x magnification

Click to expandSeal on the parchment Waitangi sheet, 55 x magnification

Stable conditions are key to how the exhibition protects the documents. Fluctuations in environmental conditions can be very problematic for inks and parchment especially. The parchment needs to maintain its shape to protect the inks and seals from further cracking.

We have a facility to match the RH of the room with the cases, so when we open the cases for maintenance or other work, such as the page changes to Te Petihana, it means the room RH will match the RH inside the case and ensure no change in the documents.

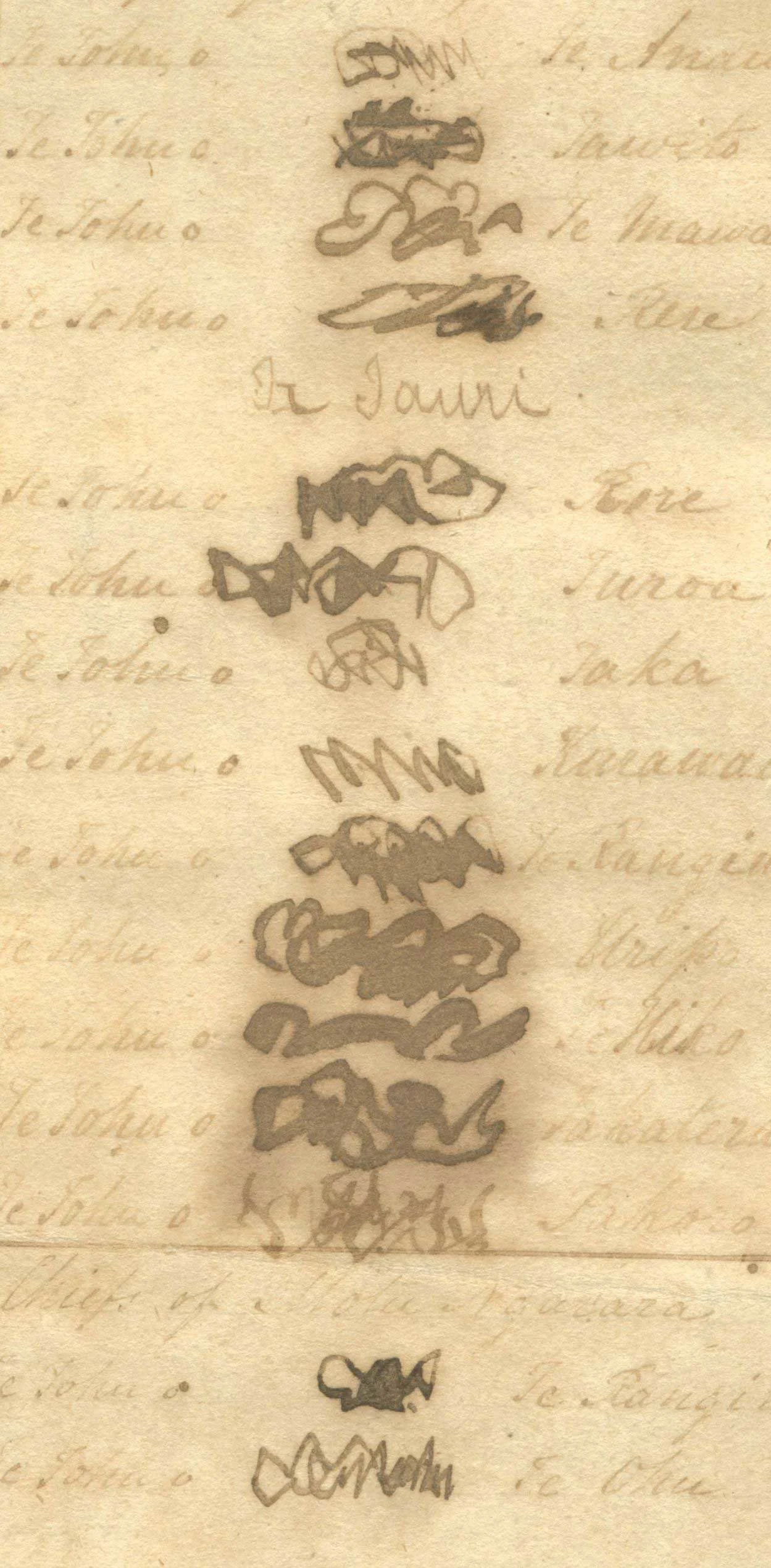

The inks

Several types of ink can be seen in the exhibition. The older documents, the 1835 He Whakaputanga and the nine sheets of the 1840 Te Tiriti o Waitangi, all have iron gall inks of varying shades from light brown to dark black. These were produced mixing iron sulphate and an extract from the galls of the oak gall wasp with gum arabic. These inks were in use for centuries because they were considered to be permanent inks. However, they could be unstable - the oxidising (the rusting of the iron component) and acidic nature of the ink can cause the paper and inks to deteriorate, the inks to corrode the paper and sometimes causing holes, often soon after being written with. This corrosion can be made worse by high or fluctuating humidity, hence the need for stable or controlled conditions for the documents. An example of this type of deterioration can be seen on the Raukawa Moana sheet in the exhibition.

-

![Writing in black ink on old yellowed paper]() Click to expandThe Raukawa Moana sheet front

Click to expandThe Raukawa Moana sheet front![Writing in black ink on old yellowed paper]() Click to expandThe Raukawa Moana sheet front

Click to expandThe Raukawa Moana sheet front -

![Black writing on old yellowed paper]() Click to expandThe Raukawa Moana sheet back

Click to expandThe Raukawa Moana sheet back![Black writing on old yellowed paper]() Click to expandThe Raukawa Moana sheet back

Click to expandThe Raukawa Moana sheet back

Fluctuating humidity can also cause physical changes. The expansion and contraction of the parchment documents previously has caused the inks on the Waitangi and Herald sheets to crack and flake because the inks sit on the surface of the parchment.

-

![cracked ink on a parchment sheet]() Click to expandSeverely cracked ink on the parchment Herald sheet, 55 x magnification

Click to expandSeverely cracked ink on the parchment Herald sheet, 55 x magnification![cracked ink on a parchment sheet]() Click to expandSeverely cracked ink on the parchment Herald sheet, 55 x magnification

Click to expandSeverely cracked ink on the parchment Herald sheet, 55 x magnification

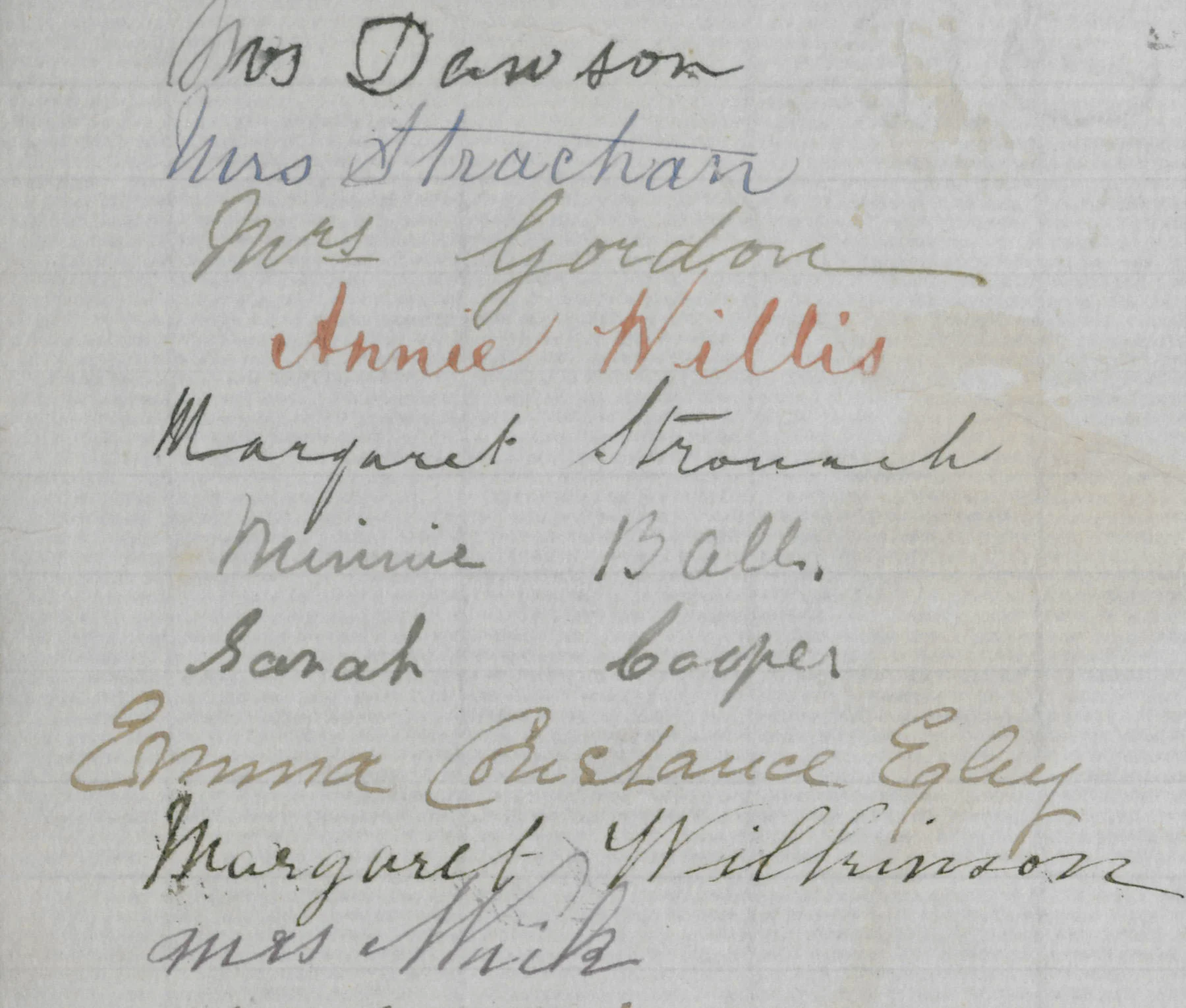

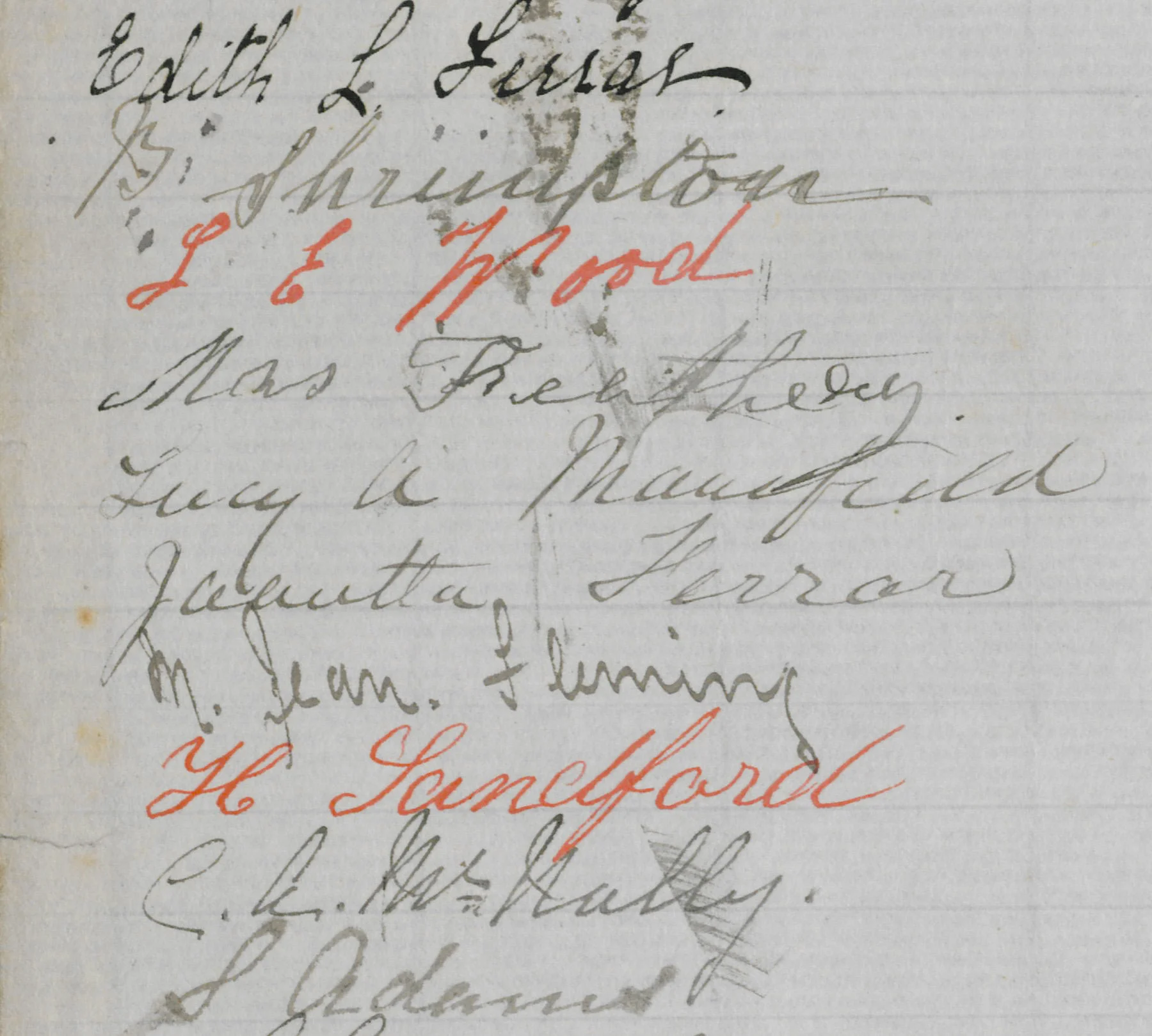

The iron gall inks used on Te Tiriti and He Whakaputanga were dated by the time Te Petihana was being signed. Many signatories used newly invented aniline inks which came in many colours and hues.

The pink, red and purple colours are especially light and water sensitive. Some iron gall inks have still been used, and have, in places, caused staining through the paper as described for the Raukawa Moana sheet above.

-

![Handwritten words written in cursive on a black yellowed paper]() Click to expandExamples of light-sensitive coloured inks on sheet 161

Click to expandExamples of light-sensitive coloured inks on sheet 161![Handwritten words written in cursive on a black yellowed paper]() Click to expandExamples of light-sensitive coloured inks on sheet 161

Click to expandExamples of light-sensitive coloured inks on sheet 161 -

![Handwritten words in black and red ink on old paper]() Click to expandExamples of light-sensitive coloured inks on sheet 257

Click to expandExamples of light-sensitive coloured inks on sheet 257![Handwritten words in black and red ink on old paper]() Click to expandExamples of light-sensitive coloured inks on sheet 257

Click to expandExamples of light-sensitive coloured inks on sheet 257

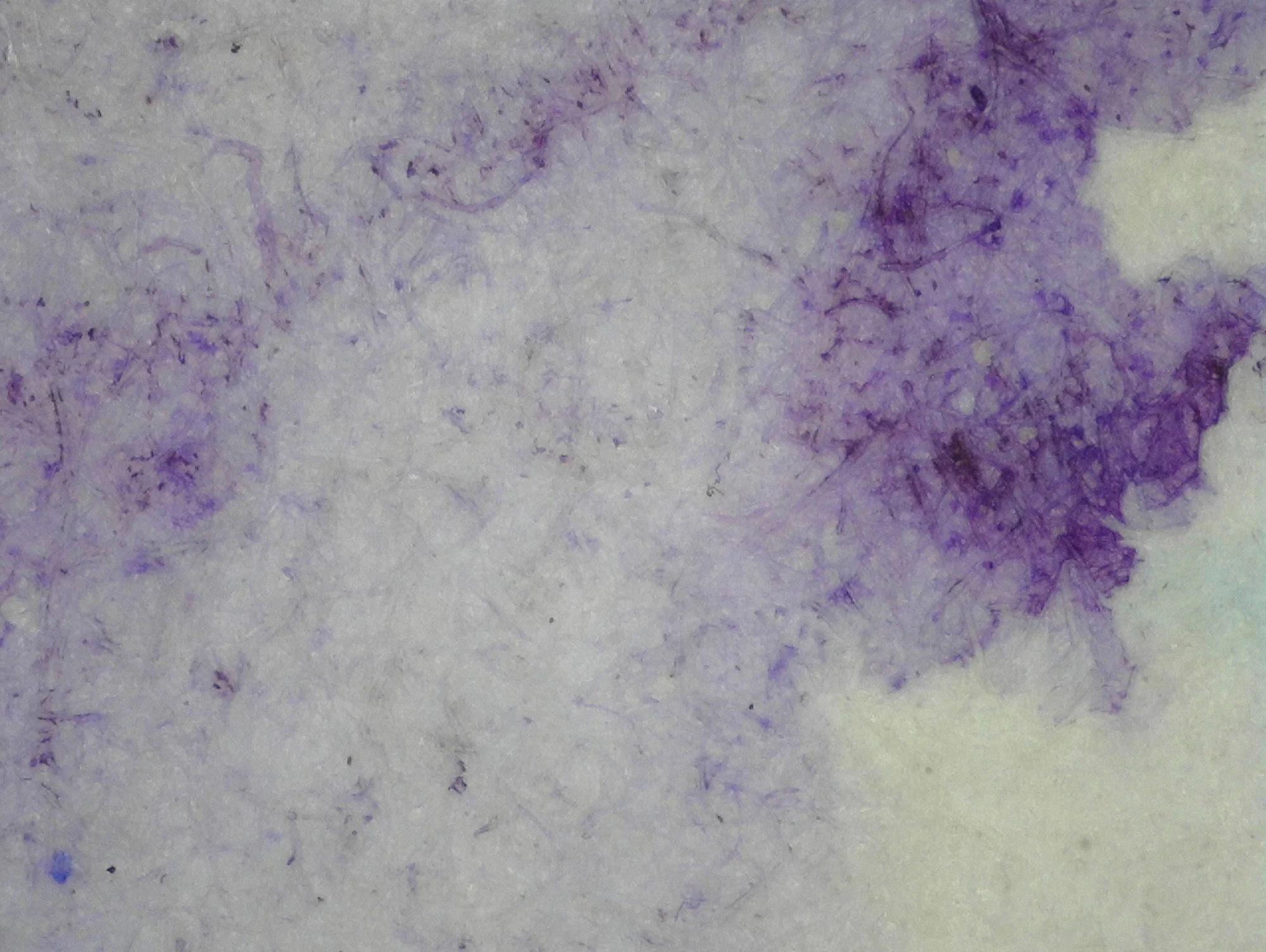

Synthetic aniline inks were developed in the 1860s from coal tar, a by-product of gas production. It was an accidental discovery during the quest to produce synthetic quinine, used to treat malaria. Many exciting new shades were made, an advance on the vegetable dyes of the past, and purple ink was especially popular. But not being water-fast caused problems. This purple ink, seen below on Te Petihana, has been smudged by water at some time.

-

![Faded purple ink on an old paper]() Click to expandPetition p 287, purple ink bleed, 100 x magnification

Click to expandPetition p 287, purple ink bleed, 100 x magnification![Faded purple ink on an old paper]() Click to expandPetition p 287, purple ink bleed, 100 x magnification

Click to expandPetition p 287, purple ink bleed, 100 x magnification

Postal services benefited from the bleeding of these inks because their stamps could not be soaked off and reused for free!

How and why are the documents mounted?

All the documents are securely mounted in one of two ways.

The Treaty documents in cases 1-3 are attached to a high quality 8-ply acid-free museum board using conservation grade paper hinges and starch paste. This is a popular technique used widely by conservators in museums and galleries for mounting paper material. It is visually unobtrusive and is fully reversible.

-

![Two hands wearing white gloves sticking a tape to an old paper]() Click to expandAttaching the paper hinge into positionPhoto by Mark Beatty

Click to expandAttaching the paper hinge into positionPhoto by Mark Beatty![Two hands wearing white gloves sticking a tape to an old paper]() Click to expandAttaching the paper hinge into positionPhoto by Mark Beatty

Click to expandAttaching the paper hinge into positionPhoto by Mark Beatty

There are several reasons why this has been done:

Wellington’s risk of earthquakes. Mounting prevents movement of the documents in an earthquake.

To facilitate safe moving and handling of the documents by avoiding touching the original. This moving and handling may occur during annual monitoring checks, case maintenance, or in an emergency evacuation.

The parchment of the Waitangi and Herald sheets is very hygroscopic (it absorbs water easily) and reacts quickly to the slightest change in relative humidity by curling. Mounting prevents this.

Te Petihana is mounted to a specially made steel rig and the displayed pages are held flat on the museum board with detachable acrylic clips incorporating magnets. When it is time to change the display, the rig can be lowered horizontally out through a ‘back door’ – it is quite heavy and requires two people to guide it down. Then the clips can be removed, and the pages changed.

He Whakaputanga is attached to the board in the same way as the documents in cases 1-3. The paper is lightweight so there weren’t any problems with presenting the pages vertically, being the optimum viewing experience. Black magnetic framing bars hold the museum board in position.

This work took place in the Archives New Zealand conservation laboratory.

-

![A woman working in a lab on a rolled up scroll]() Click to expandAn Archives New Zealand conservator joining up the Women’s Suffrage Petition scrollPhoto by Simon Jay

Click to expandAn Archives New Zealand conservator joining up the Women’s Suffrage Petition scrollPhoto by Simon Jay![A woman working in a lab on a rolled up scroll]() Click to expandAn Archives New Zealand conservator joining up the Women’s Suffrage Petition scrollPhoto by Simon Jay

Click to expandAn Archives New Zealand conservator joining up the Women’s Suffrage Petition scrollPhoto by Simon Jay

Did you know this about the documents?

He Whakaputanga/The 1835 Declaration of Independence

This document consists of two sheets of paper written on three of its four sides. We wanted to display both the signed and unsigned sides of the paper, so we commissioned life-sized replicas to show the unsigned sides. Can you tell which is which (without looking at the label!)?

The replicas were created by the artist who made the fonts and maps in The Lord of the Rings films.

Daniel Reeve: artist, calligrapher, cartographer

Te Tiriti o Waitangi/The Treaty of Waitangi

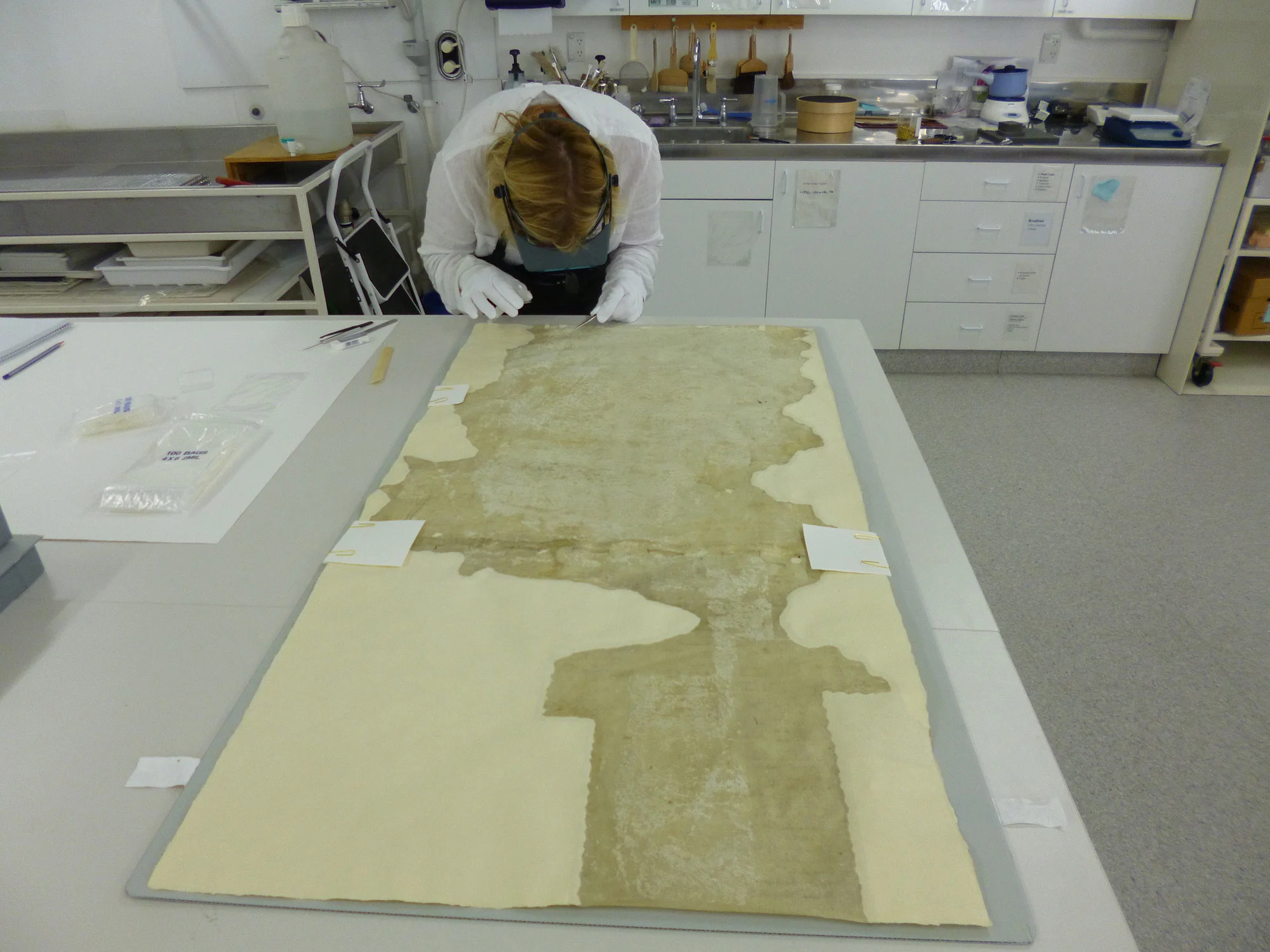

The Waitangi and Herald sheets are written on parchment, which is a kind of animal skin that has been produced in a different way to leather. We didn’t know what animal it had come from because it was so badly degraded. We had the skins DNA tested, and the two membranes of the Waitangi sheet were both found to be sheep skin, specifically from ewes. The Herald sheet’s DNA has not yet completely given up its secrets – it could be from either cattle or sheep.

-

![A conservator bending down on a table that has an old sheet]() Click to expandDNA sampling of the Waitangi sheetPhoto by V-A Heikell

Click to expandDNA sampling of the Waitangi sheetPhoto by V-A Heikell![A conservator bending down on a table that has an old sheet]() Click to expandDNA sampling of the Waitangi sheetPhoto by V-A Heikell

Click to expandDNA sampling of the Waitangi sheetPhoto by V-A Heikell

Te Petihana/The 1893 Women’s Suffrage Petition

Te Petihana is approximately 274 metres long and weighs more than 7 kilograms. It was taken into Parliament in a wheelbarrow! Having variously been in six parts, then four more recently for conservation and digitisation work, we finally joined it together before the He Tohu exhibition opened.

-

![Statue on a wall of a group of women and green leaves in the front]() Click to expandKate Sheppard National MemorialPhoto by Donna Robertson, Christchurch libraries

Click to expandKate Sheppard National MemorialPhoto by Donna Robertson, Christchurch libraries![Statue on a wall of a group of women and green leaves in the front]() Click to expandKate Sheppard National MemorialPhoto by Donna Robertson, Christchurch libraries

Click to expandKate Sheppard National MemorialPhoto by Donna Robertson, Christchurch libraries

He Tohu

A new pamphlet is released on the sixth anniversary of the Official Opening of He Tohu in 2017 describing the conservation work that keeps the documents safe.

Download the pamphlet (PDF, 7MB)

A hard copy can be obtained from the reading room at Archives, as well as at the He Tohu exhibition.

Photos - All photos by A Whitehead, except where stated.