Te Petihana mō te Reo Māori me tōna pūtaketanga mai

The Māori Language Petition and how it happened

In 1972 more than 30,000 people signed a petition asking the government to support the teaching of te reo Māori in schools.

Te reo Māori — the Māori language

Te reo Māori, the language of the Māori people of Aotearoa New Zealand, is a taonga (treasure), essential to the expression of Māori culture. Te reo Māori is an important part of Māori identity.

Origins of te reo Māori

The Māori language evolved in New Zealand over hundreds of years. Dialects vary by region because of:

isolated local communities

Māori ancestors coming from a range of different islands in eastern Polynesia.

Te reo Māori was the main language spoken in New Zealand at the beginning of the 19th century. Most early European settlers spoke the language as they depended on Māori for many things, including trading.

Declining use of te reo Māori

By the early 1860s, most of Aotearoa’s population was Pākehā (non-Māori). As a result of this, English became New Zealand’s dominant language.

Māori were encouraged to learn English to assimilate with the wider community. Speaking te reo Māori was discouraged. Schools punished many Māori for speaking their own language.

Use of te reo Māori soon narrowed to more isolated Māori communities. By the mid-20th century, many feared the language was dying out.

As the Pākehā population grew, the colonial government emphasised the use of English more.

In 1867, the Native Schools Act was passed, which was designed to assimilate Māori into Pākehā society. The Act required English to be the only language written or spoken. Under the Act, schools discouraged Māori children from learning their language and punishments were common for children who spoke te reo Māori at these schools.

By the turn of the century, many believed that speaking te reo Māori would prevent Māori from successfully learning English, stopping them from participating in Pākehā (English) society. After generations of punishment for speaking te reo Māori, people began discouraging its use, even in the home.

By 1953, the percentage of Māori schoolchildren who were able to speak te reo Māori had dropped to 26 per cent, a 64 per cent decline over 40 years.

Te Petihana Reo Māori the Māori Language Petition

Despite its suppression, te reo Māori survived. But many Māori leaders recognised there was a legitimate danger of losing the language. In the 1970s several groups formed to:

revitalise the Māori language

change attitudes towards te reo Māori

support political issues — including land and te Tiriti o Waitangi rights.

In 1972, 3 groups — Ngā Tamatoa, Huinga Rangatahi the New Zealand Māori Students’ Association, and the Te Reo Māori Society — worked together to deliver a petition to Parliament to promote the Māori language.

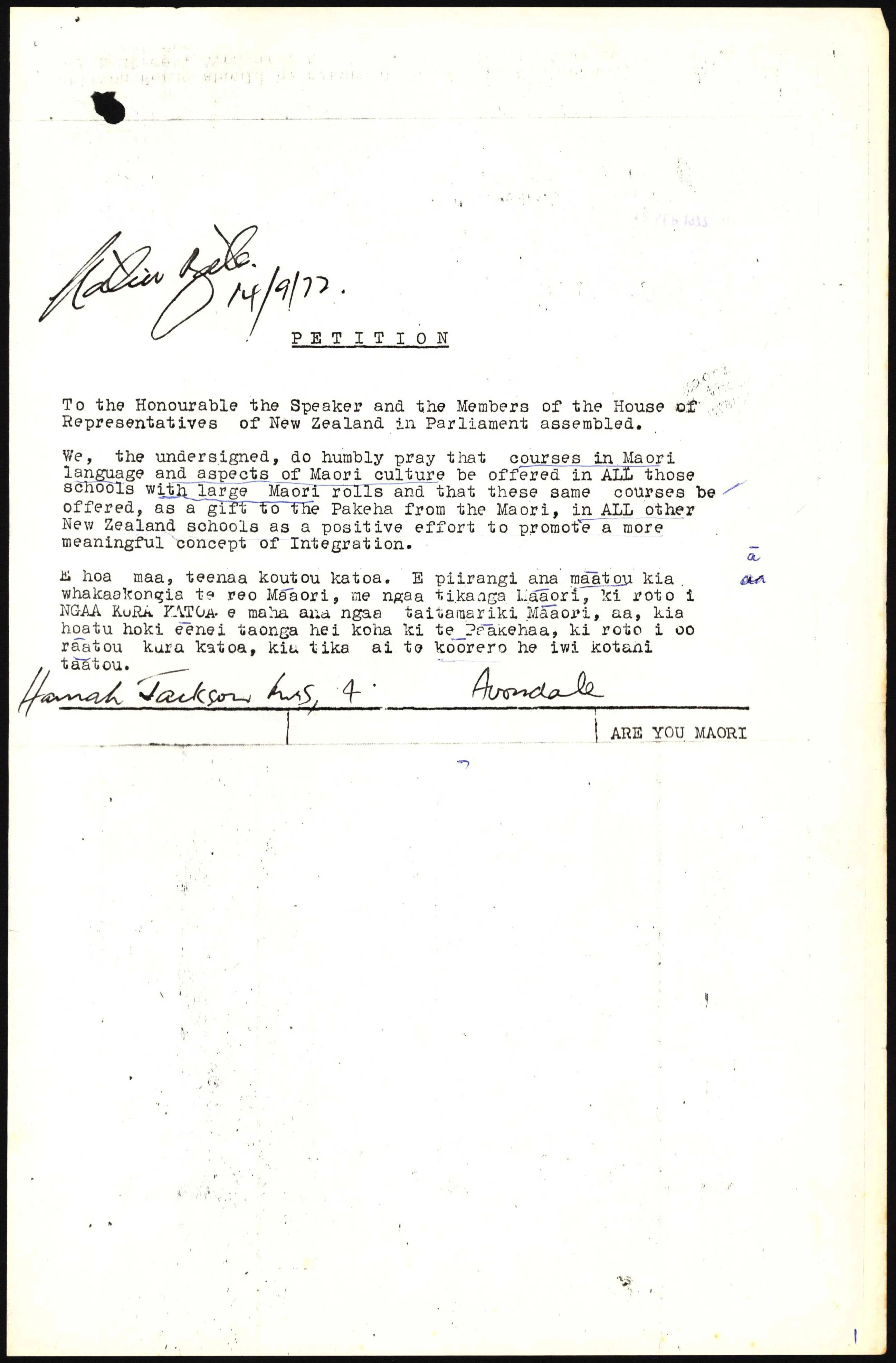

What the Māori Language Petition asked for

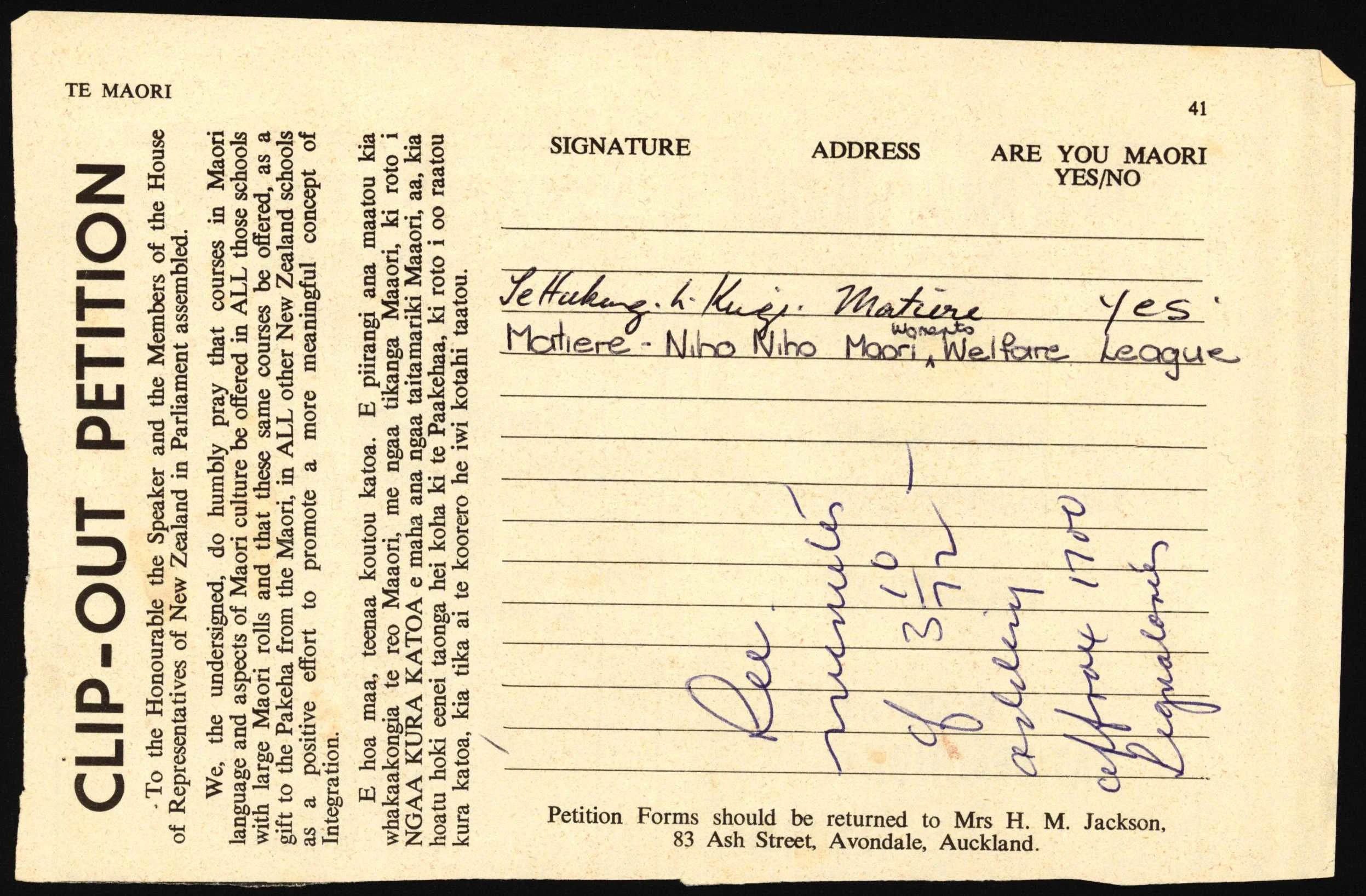

The Māori Language Petition — known in te reo Māori as Te Petihana Reo Māori — called for the New Zealand government to offer Māori language in schools. It requested that schools with large Māori rolls offer courses about Māori language and aspects of Māori culture. It also asked that the same courses be offered at other schools as a gift to Pākehā from Māori.

-

![A letter with handwritten signatures on an old paper]() Click to expandParliamentary Petitions - Mrs HM Jackson and 30000 OthersABEP 7749 1889 R17926429

Click to expandParliamentary Petitions - Mrs HM Jackson and 30000 OthersABEP 7749 1889 R17926429![A letter with handwritten signatures on an old paper]() Click to expandParliamentary Petitions - Mrs HM Jackson and 30000 OthersABEP 7749 1889 R17926429

Click to expandParliamentary Petitions - Mrs HM Jackson and 30000 OthersABEP 7749 1889 R17926429

Who worked on the Māori Language Petition

Hana Jackson

The Māori Language Petition was instigated by Hana Jackson (née Te Hemara). Of Te Āti Awa, Ngāti Toa, Ngāti Raukawa and Ngāi Tahu descent, Jackson was 22 years old when the petition was presented.

Ngā Tamatoa

Jackson was a member of the activist group Ngā Tamatoa (The Young Warriors). The group formed after the Young Māori Leaders Conference in 1970. Ngā Tamatoa campaigned for Māori culture and language and wanted Te Tiriti o Waitangi ratified.

Te Reo Māori Society

Formed in 1969 at Victoria University of Wellington, Te Reo Māori Society aimed to address the declining number of native te reo Māori speakers.

Te Huinga Rangatahi

Te Huinga Rangatahi, the New Zealand Māori Students’ Association, was a group formed in 1972 from the New Zealand Federation of Māori Students.

Signatures for the Māori Language Petition

With support from elders, the Māori Language Petition was led by Māori youth. Jackson said they ‘were trying to build a better country’.

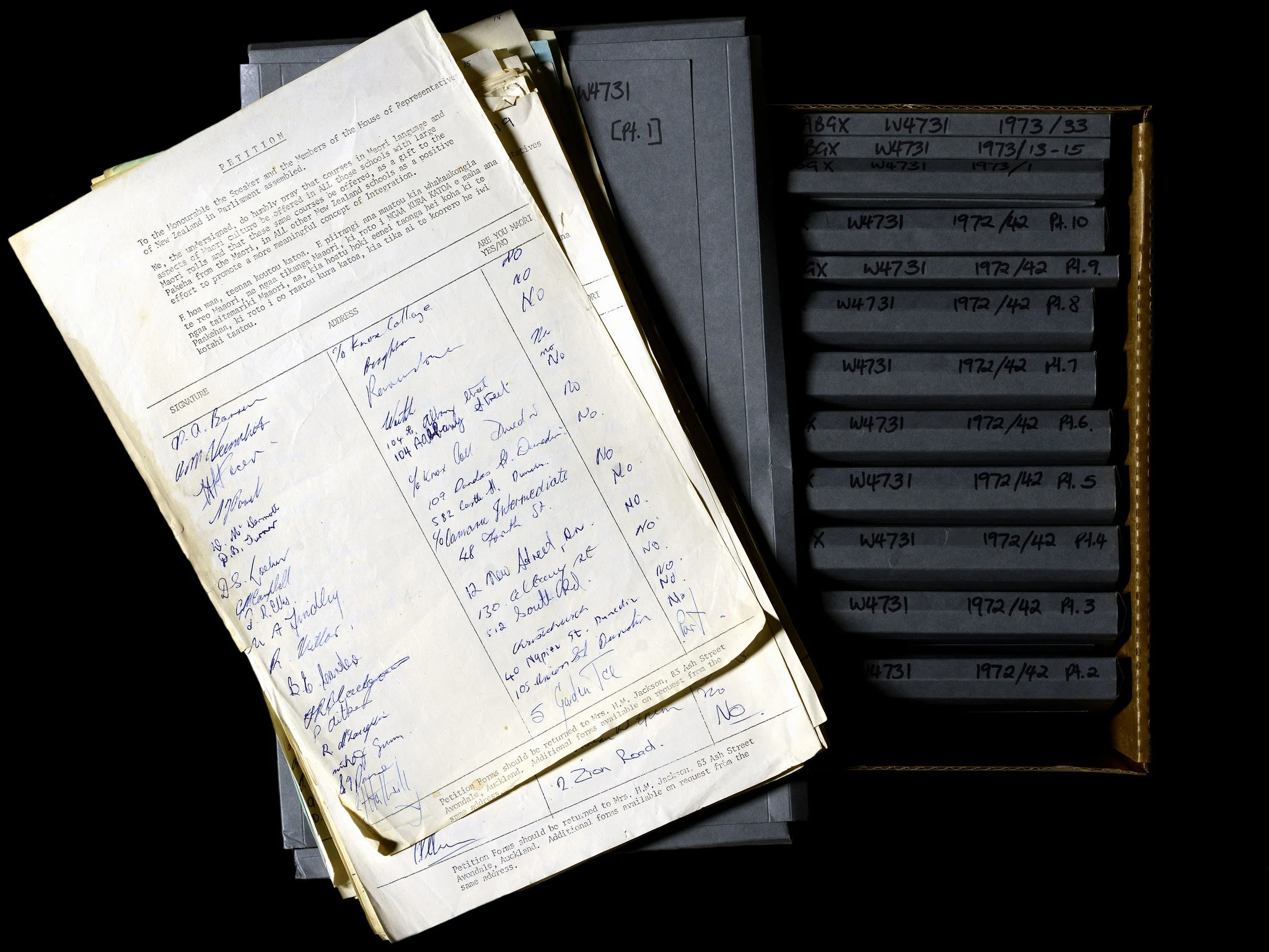

Ngā Tamatoa worked with Te Reo Māori Society and Te Huinga Rangatahi to gather petition signatures from early 1972. They collected over 30,000 signatures from people supporting the call for te reo Māori to be taught in schools. Most of the people who signed the petition were Pākehā.

-

![Bunch of old papers with handwritten signatures on a black background]() Click to expandPetition to introduce te reo Māori in schools, 1972

Click to expandPetition to introduce te reo Māori in schools, 1972![Bunch of old papers with handwritten signatures on a black background]() Click to expandPetition to introduce te reo Māori in schools, 1972

Click to expandPetition to introduce te reo Māori in schools, 1972

Delivering the Māori language petition to parliament

The Māori Language Petition was delivered to Parliament on 14 September 1972.

In the submission that accompanied the petition, Jackson said (in Māori):

“For us to be able to speak Māori is the truest expression of our Māoritanga. It is the substance of our Māoritanga. It is our link with the past and all its glories and tragedies. It is our link with our tipuna.”

Te Ōuenuku (Joe) Rene led the group who presented the petition. The Ngāti Toa kaumatua (Māori elder) performed the ‘tuku taonga’ over the petition using a patu parāoa (club).

Jackson submitted the petition to Matiu Rata, the Member of Parliament for Northern Māori, who tabled it in the House of Representatives. The petition was then referred to the Education Select Committee for review. On 12 October, the committee’s chair, John Chewings, delivered a report back to the House. The committee's recommendation was to forward the petition to the Government for favourable consideration. A motion to this effect was subsequently proposed and adopted.

Te Wiki o te Reo Māori

To mark the event, 14 September was declared Māori Language Day and eventually expanded to what we now know as Māori Language Week.

This day extended to Te Wiki o te Reo Māori (Māori Language Week) in 1975. It continues today as an annual celebration for all New Zealanders to embrace and celebrate the Māori language.

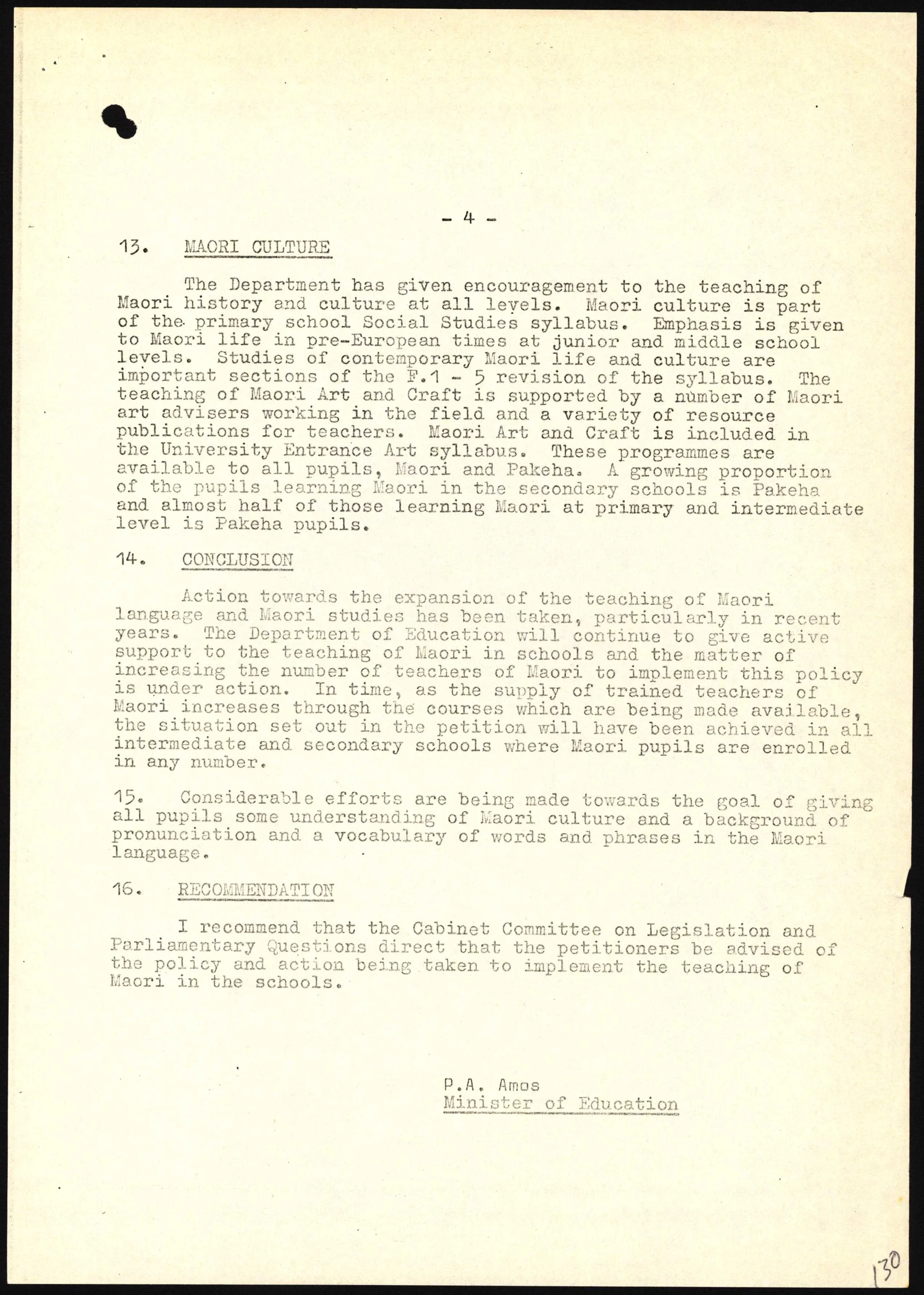

What happened after the Māori Language Petition

Historian Aroha Harris highlights that the 1972 Māori Language Petition was a crucial moment for the revitalisation of te reo Māori. The petition led the government to introducing Māori language teaching in primary and secondary schools, though initially as an optional subject, and to establish a one-year training course for native speakers to address the shortage of qualified teachers. Following the petition, Māori communities continued to advocate for more official support and launched several key initiatives including:

kōhanga reo (language immersion preschools)

kura kaupapa Māori (Māori-immersion schools)

iwi radio stations

Māori television.

All of these initiatives played a significant role in promoting and preserving the Māori language.

-

![A letter typed with a typewriter on an old, yellowed paper]() Click to expandParliamentary petition no 72/42Mrs H M Jackson and 30000 othersABEP 7749 1889 R17926429

Click to expandParliamentary petition no 72/42Mrs H M Jackson and 30000 othersABEP 7749 1889 R17926429![A letter typed with a typewriter on an old, yellowed paper]() Click to expandParliamentary petition no 72/42Mrs H M Jackson and 30000 othersABEP 7749 1889 R17926429

Click to expandParliamentary petition no 72/42Mrs H M Jackson and 30000 othersABEP 7749 1889 R17926429

Waitangi Tribunal heard the Te Reo Māori claim

In 1985 the Waitangi Tribunal heard the historic Te Reo Māori claim. This asserted that te reo Māori was a taonga the Crown was obliged to protect under the Treaty of Waitangi.

The Waitangi Tribunal found in favour of the claimants and recommended a number of legislative and policy remedies. One of these was the Māori Language Act 1987.

Māori Language Act 1987

Te reo Māori was made an official language of Aotearoa New Zealand on 1 August 1987, when the Māori Language Act came into force. The Act also established Te Taura Whiri i te Reo Māori the Māori Language Commission to promote the use of Māori as a ‘living language’ and ‘an ordinary means of communication.’

View the Māori Language Act (1987)

In 2016, the Māori Language Act 1987 was repealed by section 48 of the Māori Language Act 2016. However, there were no major changes just new provisions added and a change in language.

Te reo Māori today

Today, a number of strategies led by Māori and the Crown are in place to strengthen the use of te reo Māori.

Strategies to strengthen use of te reo Māori

Maihi Karauna — focuses on creating conditions for te reo Māori to thrive and ensuring government systems support this. With the main goals being:

5% of New Zealanders (or more) will value te reo Māori as a key part of national identity.

1 million New Zealanders (or more) will have the ability and confidence to talk about basic things in te reo Māori.

150,000 Māori aged 15 and over will use te reo Māori as much as English.

Maihi Māori - is developed by and for Māori to lead their own revitalisation efforts. This strategy focuses on the restoration of te reo Māori as a first language for the next generation of Māori.

Read more information on the Māori Language Strategy - Te Taura Whiri i te Reo Māori

A forever language

“Under enduring pressure te reo Māori has shown it will adapt and survive. It grows with our people, our culture and our environment.”

— Te Taura Whiri i te Reo Māori

Since the 1980s, numerous institutions dedicated to the recovery of te reo Māori have been established. Although significant progress has been made, including the recognition of Māori as an official language of New Zealand through the Māori Language Act 1987, the decline of the language has only recently been halted.

While the original goals of the 1972 petition have yet to be fully realised, the efforts of the petitioners have inspired many positive changes. While every school does not offer te reo Māori, the legal status granted by the Māori Language Act 1987, marks a major milestone. The legacy of the petitioners continues as many dedicated individuals and organisations strive to achieve the objectives originally set out. Many now continue the petitioners’ mahi (work), and are determined their objectives will be achieved.

View the Māori Language Petition

As part of our role as guardian of over 7 million records created by government and public institutions of Aotearoa New Zealand, we work to preserve and protect the original Māori Language Petition documents.

The Office of the Clerk of the House of Representatives transferred the petition to us as part of their records. It is now safely stored in our Wellington archive and digitised so you can view it online, any time, anywhere.

View the Māori Language Petition on Collections search

View the submissions regarding Māori Language Petition on Collections search

-

![Black text and handwritten signatures on an old paper]() Click to expandPage from Te Petihana Reo Māori The Māori Language PetitionABGX 16127 152 R18369539

Click to expandPage from Te Petihana Reo Māori The Māori Language PetitionABGX 16127 152 R18369539![Black text and handwritten signatures on an old paper]() Click to expandPage from Te Petihana Reo Māori The Māori Language PetitionABGX 16127 152 R18369539

Click to expandPage from Te Petihana Reo Māori The Māori Language PetitionABGX 16127 152 R18369539