Report on the State of Government Recordkeeping 2020/21

Chief Archivist’s Foreword

E ngā minita, me ngā Kaiwhiriwhiri o te Whare Pāremata – tēnā koutou, tēnā koutou, tēnā koutou katoa.

It is astonishing the difference a decade can make. In 2010, Aotearoa New Zealand’s early tech adopters scrambled to be among the first to buy Apple’s groundbreaking new tablet device, the iPad. Apple’s original disruptor, the iPhone, was becoming mainstream as Kiwis snapped up the new iPhone 4.

At that time the Public Records Act 2005 had been in force for only five years, and the five year ‘grace-period’ for compliance with the new recordkeeping standards and recordkeeping audits was over. As social media took off in Aotearoa, thanks to the popularity of smart phones and digital devices, Archives New Zealand Te Rua Mahara o te Kāwanatanga (Archives) was putting the finishing touches on its first recordkeeping audit report under the new legislation. I remember this clearly, as it was also the same time I left Archives, after a five year stint, to take up another role in the public sector. I went from gamekeeper to poacher, directly from the team designing the standards and audit programme to the team in an agency leading the response.

In the decade since, we’ve all seen transformative change through technology, both personally and professionally. We back up our memories as digital photos stored in the cloud. We live our lives online and leave a digital footprint when we die. At work, we generate numerous emails, documents and video conference meeting recordings. The global pandemic may have necessitated working from home but it is digital technologies, such as Zoom and Microsoft Teams, that have made this remarkable shift possible.

For those of us who work in the public sector, this has made a huge impact on the way we create and manage information. The world has moved on, but the evidence suggests that our recordkeeping processes, policies, platforms and practice have not. We are lagging behind.

Archives is establishing a new Information Management (IM) monitoring framework. The annual survey of public sector information management and audit reports will now run in tandem, so together they provide an all-of-government view and a benchmark of individual organisations’ progress respectively. Meanwhile the new IM Maturity Framework helps both auditors and regulated parties assess their maturity level of IM practice. We also have an IM Standard that sets out expectations for agencies.

The key findings from the 2020/21 annual survey, and the first cohort of audits from the new audit programme, show that change continues to be slow. In fact, in core categories such as IM staff capability and disposal implementation, there has been little improvement or even regression over the past decade since our 2010 survey. In the fast-paced data-driven age, standing still is going backwards.

Government recordkeeping has not kept pace with technological advances. Public offices and local authorities now create the majority of records in digital format, data growth is exponential, while the office printers are still as busy as ever. Most public sector organisations hold countless copies of all their documents and data, digital and physical. This proliferation, and ‘keep everything’ approach creates an unmanageable ‘digital landfill’, making it difficult to distinguish what has value from the mass.

To start to gain some control over this information quagmire, we need an appraisal and disposal system designed for the digital age. This year the team behind our Appraisal, Disposal and Implementation (ADI) redesign project began looking at the technology and tools that IM professionals need to assess and manage their records efficiently, whilst meeting their legislative obligations. The volume, variety and velocity of data is now beyond what humans can process. We need automated rules and algorithms to apply retention and disposal policies efficiently. This requires a cultural shift and behavioural change to accept that it is impossible to check over every digital file before disposing of what is not needed.

When it comes to appraising documents, we recognise that, as archivists and IM professionals, we need to be more open-minded about which documents we keep. Historically, Archives has tended to keep government records for strategic reasons, top-down macro-appraisal. We are increasingly realising the importance of keeping records from the perspective of the individual, or community, rather than the state, that tell stories about us as people, as sub-cultures and as Iwi, particularly those whose stories were once unlikely to be preserved.

In the past, Te Ao Māori concepts were not included in our IM practice. This led to the current situation where public sector organisations are unable to find the data and information that is of interest and value to Māori. This also makes them inaccessible to agencies to fulfil their Tiriti obligations and to Māori. Our system of government and recordkeeping systems were imported wholesale into Aotearoa from Europe, but we have an opportunity to change that.

Nowhere was this situation highlighted more clearly, in the last year, than during the Royal Commission of Inquiry into Historic Abuse in State Care and in the Care of Faith-based Institutions (Abuse in Care Inquiry). The many hearings and investigations that took place in 2020/21 showed, time and time again, that Māori and other individuals who are trying to locate personal information held by one or more government agencies are unlikely to know where to look.

The Abuse in Care Inquiry, and the survivors’ stories and personal accounts, has underlined the criticality of our purpose within a well-functioning democracy. We are here to care for the records that hold government to account, and to uphold transparency, and where necessary the means of seeking redress. It is our mission to support open government principles, and the appropriate IM practices that may achieve this.

Archives, in its work supporting the Royal Commission, has an intention to listen and learn from the past. Has there been poor recordkeeping? What might have contributed to that? Much changed in public recordkeeping practices between 1950 and 1999, the years that are the Inquiry’s focus. But have the changes to the regulatory framework been enough to prevent us repeating previous mistakes? Are there still some gaps that we need to address?

Archives is committed to learning the lessons of past recordkeeping failures, highlighted by the commission and we are looking to integrate these insights into our mahi, in projects such as our appraisal and disposal redesign and in looking at an all-of-government ontology. An ontology, or shared conceptual information model, is a mechanism to put people at the heart of government information models, not the agency creating it.

Our work in supporting the Inquiry highlights the importance of the regulatory framework and the mandatory requirements of all public offices. The Inquiry has shown the importance of creating and maintaining full and accurate records of decisions, policy and practice, and the need to understand the value of information in the records. We are also looking at what regulatory levers we can use to guarantee a consistent and meaningful engagement with Iwi and other Māori leaders. This will ensure Māori perspectives on the significance and value of information are considered as part of an agency’s appraisal and disposal decisions.

We need a step change in approach, this extends to other areas of our responsibilities such as the Tāhuhu: Preserving the Nation’s Memory (Tāhuhu) programme, which includes the upgrade and construction of modern, purpose-built facilities designed to preserve New Zealand’s documentary heritage. Currently, more than 60% of Archives and National Library buildings in the North Island are not fit-for-purpose. Despite seeing exponential digital growth, it seems likely that we have yet to hit peak paper, given we still need to manage and store decades’ worth of paper records. Archives Wellington has been full since 2017 and this is the reason for our current transfer suspension, although we are open for digital transfers. Therefore, we also need to build capacity and capability for digital transfers to offset this.

At the time of writing, Aotearoa New Zealand is in lockdown due to a COVID-19 outbreak of the virulent Delta strain. Many people, including public sector staff and IM professionals, are, yet again, working from home. Thanks to technology, the peoples of the land of the long white cloud are working in the cloud. But whether we record information in emails or via video calls on Teams or Zoom or instant messaging apps, we must manage it. The principles of government recordkeeping remains the same; the records of government, our nation’s collective memory, must be maintained, regardless of format.

On a personal note, it’s been a really exhilarating and challenging first year back in Archives New Zealand, after 10 years working across a range of public sector agencies. As a professional archivist and records manager, and public sector Chief Data Officer, I really understand the challenges that are faced by both perspectives: the agency information/data managers; and those on the archives regulatory and curation side. My mission, as I see it, is to close that gap, and bring us closer together in this shared all-of-government enterprise of managing the memory of the nation. I realise this important endeavour has to add value to both partners, so agencies getting greater value from their data is just as important as archives getting data for long-term preservation and access. What they both have in common, is serving our communities, and maintaining our social contract.

Getting value from our memory, information and taonga to make New Zealand a fairer, safer and more equitable place is what inspires me professionally, maintaining our past to inform our future – kia whakatōmuri te haere whakamua.

This is where Archives adds value to New Zealand, and the Public Service, through having a memory we can recall, to make better decisions to enhance our service delivery to our people. We preserve the past to inform the present, to achieve a better future. Business intelligence and predictive analytics rely on good quality information from our previous work, to give insight to the present, to better predict what will work into the future.

There is no excuse for poor record-keeping in the digital age when we have the right processes and tools available. Good practice will ensure that we can maintain our current holdings of almost eight million official records in a way that means they are safeguarded, yet accessible to all, and continue to add to them. If we can preserve and protect our holdings, and democratise them, current and future generations can access our unique stories, taonga and heritage, whatever their motivation or need and be empowered, to tell their own stories.

Ngā mihi whānui ki a koutou katoa

Stephen Clarke

Chief Archivist - Kaipupuri Mātua

Executive Summary

Archives New Zealand Te Rua Mahara of te Kāwanatanga works to ensure effective, trusted government information for the benefit of all New Zealanders. Our goal is for all New Zealanders to easily access and use this taonga, connecting you to your rights and entitlements – now and in the future.

The Public Records Act 2005 (PRA) establishes the statutory role and duties of the Chief Archivist, which includes exercising a leadership role of information management across public offices and setting standards for public sector information management.

The past year has been another challenging one for both our nation and the world due to the global COVID-19 pandemic. In 2020/21 our borders stayed closed and the varying alert levels kept many of us working from home. In many ways it was another year of stasis. Likewise, the information management (IM) sector appears to be in idling mode – ticking over from the previous year.

The key findings from the Survey of Public Sector Information Management 2020/21 show some patterns of improvement, which is positive, but the level of improvement is not significant. Equally we are seeing areas with a downward trend, which is a concern. It might be tempting to blame some of this on COVID-19, given that both the 2019/20 and 2020/21 survey reflect flat levels of improvement. But the 2018/19 results give us a longer view.

Archives New Zealand recognises that fundamental difficulties and barriers remain within the IM sector and we are looking at ways to help to solve these as the regulator. The 2020/21 Survey also found that both levels of IM staffing in public offices, particularly, and the percentage of public sector organisations that have built IM requirements into new business systems remain low and are dropping.

It is crucial that we and our regulated organisations get the disposal system working. Currently, the overall system is not working as it should in enough organisations. The system, as it currently stands, is largely based in a pre-digital paradigm and often won’t work for digital records. The inability to identify what has value, has led to a ‘keep-everything’ mindset, thereby forming a digital landfill.

Report on audits conducted under Section 33 of the Public Records Act 2005

Introduction

2020/21 marks the first year of a new and ongoing audit programme. It is the second round of audits to take place under PRA. The approach has devolved and gaps identified in the initial programme have been addressed.

Since the previous audit programme finished in 2014/15, we have refreshed the programme to provide more benefit for all involved. This will support tangible improvement – both in public offices’ IM practices and Archives New Zealand’s monitoring approach. The audit programme is part of our leadership role in regulating IM across the government sector.

A PRA audit gives a point-in-time snapshot of the core IM practices of a public office. It is a chance to show an organisation’s IM strengths, and to see where there are opportunities for improvement. We are using our newly developed IM Maturity Assessment as the framework for the audit process which gives consistency across the sector with scaling as appropriate to the size of the organisation and value of their information. Archives releases audit reports on our website. This provides transparency and accountability of organisations’ performance as well as our own regulatory effectiveness. Post-audit, we now actively follow-up with organisations to support improvement in their performance, and we conduct feedback surveys on the process (see below).

Audit is one of the key components of our Monitoring Framework, along with the annual survey of public sector IM. Each of the monitoring tools in our kete has a distinct purpose and complements each other. While audit identifies the maturity level of an individual organisation’s IM practice, the annual survey gives a sector-wide view. Meanwhile the new IM Maturity Assessment helps organisations to self-monitor their performance and identify what they need to do to improve.

Audit methodology and scope

Under Section 33 of the PRA all public offices must be audited every five to 10 years. This means that our annual audit schedules from 2020/21 to 2024/25 include organisations that were audited 10 years ago and must be re-audited. Within that constraint, and subject to resourcing, the future programme gives flexiblity to, for example, audit organisations with more high-value/high-risk information more frequently than those with less high-value/high-risk information.

The refreshed audit programme started in December 2020. The 2020/21 cohort of audits involved 31 public offices. Our auditors KPMG and Deloitte carried out 30 audits, with Wellington Institute of Technology (WelTec) and Whitireia Community Polytechnic audited together.

Audits are based on the requirements of the PRA and the Information and records management standard (the Standard) as presented in the IM Maturity Assessment. The audit programme looks at eight key areas, or categories, addressing 20 topics related to IM practice. The categories are: governance, self-monitoring, capability, creation, management, storage, access and disposal. In an audit, we ask each organisation a set of core questions based on these eight key areas.

Maturity trends in 2020/21

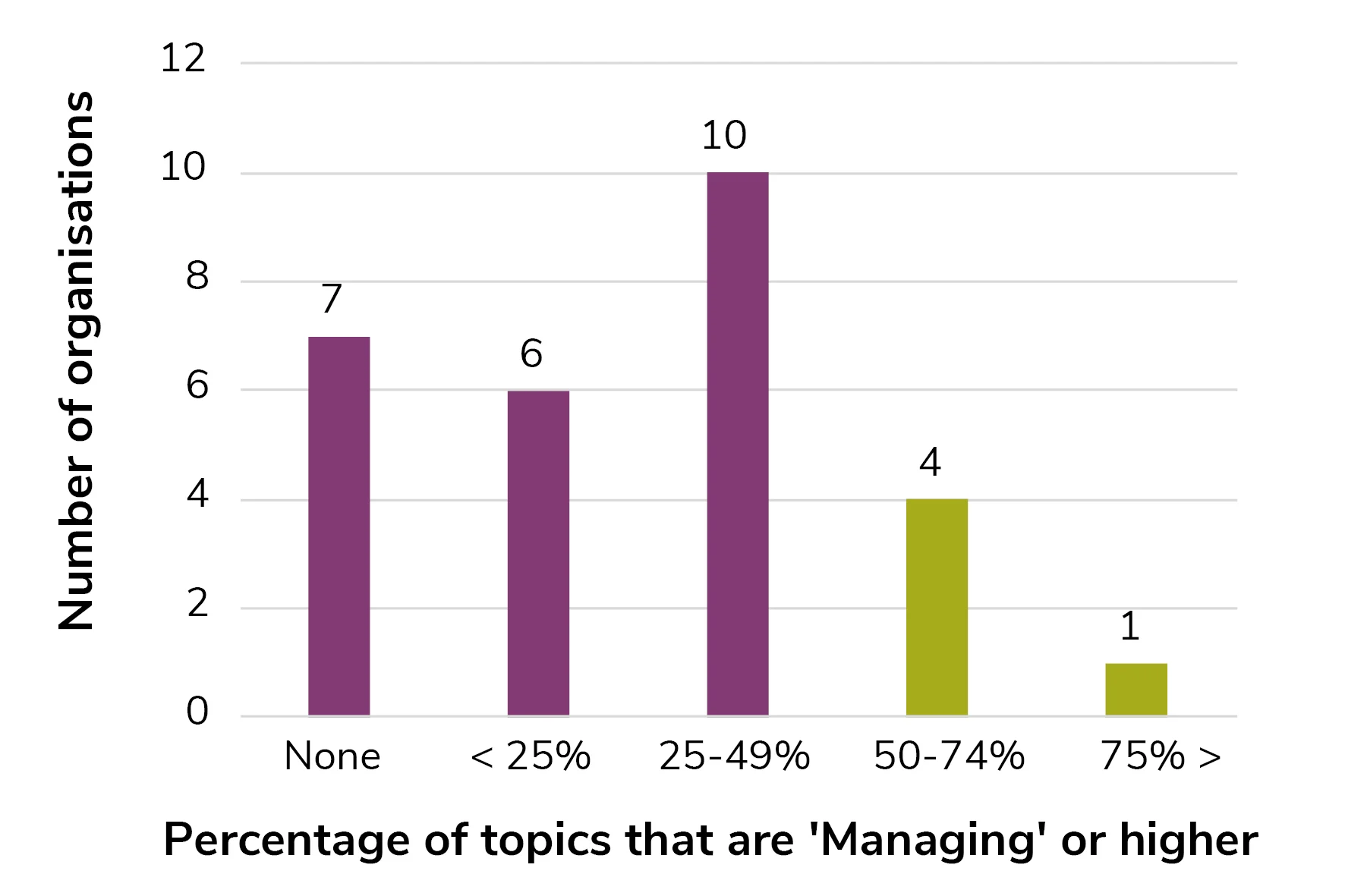

The auditors provide the organisation with a maturity rating for each topic in their final audit report. Organisations assessed as having a maturity level of ‘Managing’ across all IM topics are broadly meeting the minimum requirements set out in the PRA and the Standard. The maturity levels are: Beginning, Progressing, Managing, Maturing and Optimising. While not directly comparable with the 2010-2015 audit programme, the results and themes of 2020/21 are similar. Of the 28 organisations that have had their audit maturity ratings finalised, five achieved a rating of ‘Managing’ or higher for most topics (shaded green in Figure 1). The outstanding performer this year is the Financial Markets Authority, which achieved a rating of ‘Managing’ or higher for 17 out of 20 topics (85%). Overall, however, the results support our view that major improvements in maturity are required across the board. These results are not directly comparable to the audit ratings from the 2010-2015 audit programme, which used a different topic, scoring and rating system. However, comment was made in the Report: State of Government Recordkeeping and Public Records Act 2005 Audits 2014/15 that “it is disappointing to see that, although the Act came into force 10 years ago, barely half of the public offices audited in 2014/15 have recordkeeping maturity at or above the level of a managed approach to records management”. With just one year of the refreshed audit programme completed we are seeing similar results.

Figure 1: Percentage of topics where ‘Managing’ level of maturity is met

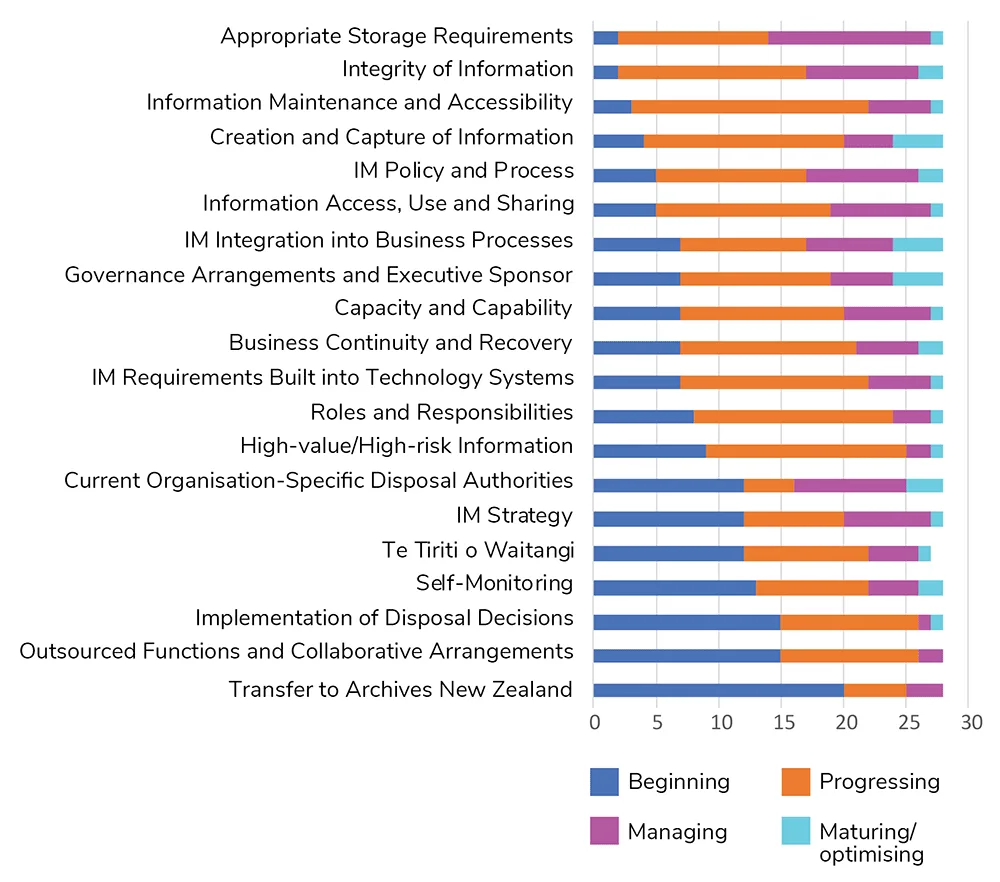

Maturity by category and topic

For the 2020/21 audits the most mature topic is storage requirements, where one organisation is ‘Optimising’ and 13 are ‘Managing’ (Figure 2). The least mature topic is transfer to Archives, where 20 out of 28 organisations only met the ‘Beginning’ level of maturity.

Governance

Within the Governance category, there is a spread of scores across the levels for the topics IM policy and processes (Topic No. 2), Governance arrangements and Executive Sponsor (3) and IM integration into business processes (4). It is important that these topics are covered well in the organisation, no matter what size, as they can provide strong foundations and support for the performance of IM across the organisation.

A few organisations are at Maturing and Optimising for IM integration into business processes. It is encouraging to have some higher maturity levels reported by the auditors and we will support sharing of this best practice with the sector.

Topics IM strategy (1), Te Tiriti o Waitangi (6) and Outsourced function and collaborative arrangements (5) are mostly at the Beginning end of the scale. Even small organisations, although not needing a complex IM strategy, still need to plan their IM direction in a dynamic digital environment. Most organisations have not identified the information that they hold that is of importance to Māori. We are seeing a lack of attention to the requirements for the management of information in contracts/agreements where functions are outsourced, or shared, and public records are created.

Self-Monitoring

Most organisations are at Beginning or Progressing level. We anticipate that the Monitoring Framework activity that Archives has been engaged in over the last few years will encourage organisations to perform their own monitoring. The data gathered can help organisations to understand their own performance and gives the opportunity to compare with others.

Capability

Topics Capacity and capability (Topic No. 8) and Roles and responsibilities (9) show results mostly below the Managing level where we expect organisations to be to largely meet the requirements of the PRA and the Standard. IM systems need to be adequately supported and staffed and audit recommendations often prompt organisations to understand what level of resource is needed to meet their business needs. For small organisations, contracting an IM resource may be the right approach. For an organisation to manage their information well, all staff need to understand their roles and responsibilities so there needs to be induction and support.

Creation

Many organisations have not identified their high-value/high-risk information (Topic No. 11) and therefore cannot prioritise their work to manage this important information including identifying and addressing any risks. When onsite, the auditors conduct staff focus groups and mostly staff attest to knowing the importance of the information they create and how to manage it. The systems provided by the organisation to capture the information and the support and monitoring of these systems also impact maturity and we encourage senior leadership to have oversight of the many aspects that contribute to robust creation of information.

Management

There are four topics in this Category: IM requirements built into technology systems (Topic No. 12); Integrity of information (13); Information maintenance and accessibility (14); and Business continuity and recovery (15). Integrity of information has the highest maturity with 40% of organisations at Managing or Maturing. Staff often report confidence that they have a consistent experience when finding and retrieving information that they create and manage. IM requirements built into technology systems has low maturity with 22 organisations at the beginning or progressing level. Some content management systems can manage automated disposal, but this is yet to be well implemented in systems.

Information maintenance and accessibility is mostly at Progressing level with many organisations not yet identifying and managing the preservation and digital continuity needs of information to an expected standard. This area also requires close collaboration between IM and ICT staff and audit interviews are conducted with both groups. The dependence of IM on effective information security was highlighted by the May 2021 cyber-attack on the Waikato DHB. The inability to access patient and corporate records severely hampered DHB services. Our auditors were coincidentally onsite at the time of the attack and the DHB has delayed completion of its audit components as it prioritised recovery. Business continuity and recovery – there are still organisations that need to identify critical information with most organisations at Progressing level. Response to COVID-19 and working from home will have had some positive impact on this topic.

Storage

Appropriate storage arrangements (Topic No. 16) has the highest maturity level of all topics. Increasingly it relates to digital storage. Many organisations use commercial third-party storage companies to store their physical records however a few still have considerable and important physical stores in-house and these are checked by the auditors when doing onsite work. IM and ICT staff are involved in audit interviews so that the auditor can get a view of the management and control of all storage environments, digital and physical. Organisations are mostly managing the considerable risks to stored information, however a breach can have a significant impact, as was seen in the Waikato DHB cyber-attack.

Access

The Information access, use and sharing topic (No. 18) relates to ongoing access to and use of information to enable staff to do their jobs. This is system related and for digital systems involves IM and ICT staff working together to ensure systems are user friendly and protected by appropriate access controls. Half of organisations are at Progressing maturity and almost one- third are at Managing maturity. Some organisations are still operating shared network drives which do not facilitate discovery nor meet minimum metadata requirements.

Disposal

This category often features in the prioritised recommendations. Auditing the topic Current organisation-specific disposal authorities (Topic No. 18) shows that around half of audited organisations have a current organisation-specific Disposal Authority (DA) which enables authorised disposal of core information. It is important to note that organisations can dispose using the General Disposal Authorities (GDAs) even if they do not have their own DA. The maturity rating for Implementation of disposal decisions (21) is among the lowest across all topics indicating that disposal using GDAs or the organisation-specific DA is not happening.

Transfer to Archives New Zealand (22) is the topic with the lowest maturity rating. The closure of our Wellington repository for physical transfers until new storage space is available is clearly one barrier to disposal. This aside, the overall view is that the disposal process, which should flow smoothly from appraisal to destruction or transfer, is not working well because of both design and implementation challenges. This is apparent in the very low number and limited size of digital transfers that Archives New Zealand and public offices have been able to complete. Archives has initiated a project to improve appraisal, disposal and implementation especially for digital records.

Figure 2: Distribution of maturity levels by topic

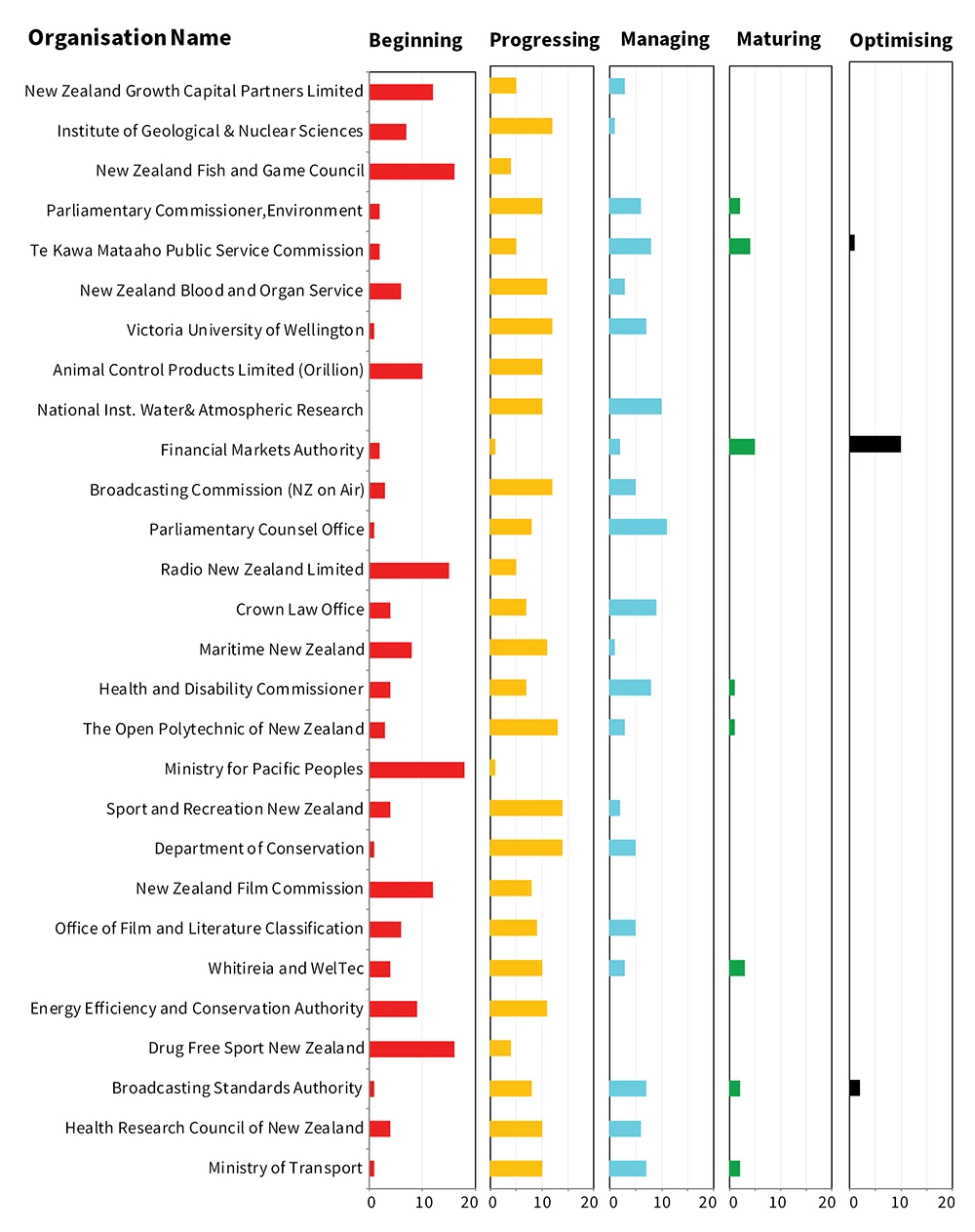

Maturity by public office

Some patterns are discernible in agency maturity, as summarised in Figure 3. The majority of the public offices audited in 2020/21 (15 out of 28 audits completed at the time of writing) have half or more of their maturity level assessments in the Progressing levels. Four organisations have 75% or more maturity level assessments in the Beginning levels. They are a varied group: Drug Free Sport New Zealand (16 out of 20 topics are at ‘Beginning’), the Ministry for Pacific Peoples (181), the New Zealand Fish and Game Council (16) and Radio New Zealand (15). Only eight organisations have any topics assessed at either of the two highest maturity levels (Maturing or Optimising).

One exception to the overall pattern is the Financial Markets Authority (FMA). With most of its maturity level assessments in the Optimising (10) and Maturing (5) levels, the FMA exemplifies sector best practice in many areas and is an example of what committed organisations can achieve in management of their information.

Following up after audits

A key lesson from the 2009/10 – 2014/2015 audit programme was that we needed to do more post-audit to support improvements to IM in individual public offices. To achieve this, we identified the need for action plans from audited organisations to address improvement recommendations from the audit report and to build formal follow-up into the audit lifecycle.

Process

Our follow-up programme kicks in after an audited organisation receives its final audit report and letter from the Chief Archivist. The letter identifies areas for improvement that should be prioritised from among the auditor’s recommendations.

Follow-up begins with a request for the organisation to prepare an action plan. The action plan sets out a schedule of activities that the organisation will undertake to address the priority recommendations issued by the Chief Archivist. The organisation has six months to submit its action plan. This is followed by a series of progress check-ins that wrap up two years after their audit.

The intention is that this process will give audited public offices a clear pathway for improvement. It will also provide the opportunity for ongoing engagement with Archives and access to support. Every public office receives follow-up, but the level of engagement will match

Follow up in 2021/22

Action plans for public offices that were audited in 2020/21 will begin coming due in late 2021. In next year’s annual report, we will be able to start reporting on progress with action plan implementation and how well this approach is going. The top three topics that we have most frequently asked public offices to address in their action plans are shown in Figure 4.

IM strategy

Features in 12 out of 15 organisations’ prioritised recommendations

Implementation of disposal decisions

Features in 11 out of 15 organisations’ prioritised recommendations

High-value and/or high-risk information

Features in 9 out of 15 organisations’ prioritised recommendations

Feedback on the audit programme

After we complete each audit we ask organisations to provide feedback on their audit experience in a short questionnaire. We ask organisations to rate different aspects of their audit experience. They can also provide general comments or suggestions.

This feedback supports continuous improvement of our audit processes, tools and outputs. It also sets expectations with our audit service providers. Audits need considerable input from organisations. We want to make sure the process goes smoothly and delivers value for them.

It is still early days for the refreshed audit programme. The feedback we have collected so far indicates that both Archives and auditors are communicating well with organisations, and auditor visits are easy to facilitate. Areas for improvements are yet to emerge. We expect to be able to report more insights in next year’s annual report as the dataset grows.

Our other regulatory work in 2020/21

Compliance trends and case studies

Archives works to ensure effective government recordkeeping for the benefit of all New Zealanders. IM is now digital, first and foremost, with most government records ‘born digital’, or created in digital format. We therefore develop our skills and expertise so that we can deliver fit- for-digital processes and guidance.

PRA does not provide Archives and the Chief Archivist with explicit investigative powers. However, our tools include the ability to direct a public office to report to us, to inspect records and to give directions about how estray records must be managed. The PRA also contains offences, notably damaging or improperly disposing of records. Potential non-compliance is assessed against the Standard and the principles of the PRA. As a regulator we use a range of approaches to enable compliance, including championing good practice and calling out non-compliance.

Good recordkeeping is crucial for accountability and transparency. Public trust is upheld when public organisations maintain a full and accurate record of how government reaches decisions that impact on the lives of New Zealanders. It is important for organisations to maintain records of their interactions and decision-making. By maintaining their records in a full and accessible state, public trust is upheld through the transparency of the government record.

The PRA intersects with several other Acts. The main ones are the Official Information Act 1982 (OIA), the Local Government Official Information and Meetings Act 1987 (LGOIMA) and the new Privacy Act 2020, which came into effect in December 2020.

In 2020/21 we continued our close working relationship with the Office of the Ombudsman, Tari o te Kaitiaki Mana Tangata. Under section 28(6) of the OIA and section 27(6) of the LGOIMA, the Ombudsman may notify the Chief Archivist when an information request has been refused by an organisation for reasons relating to IM.

Core PRA obligations are crucial during COVID-19

COVID-19 lockdowns and varying alert levels have placed pressure on public sector organisations to adapt to a new flexible work environment, and to meet the challenges that this has placed on existing information management structures.

To ensure government continues to be transparent, accountable and effective during the pandemic response, it is crucial that public offices and local government continue to create and maintain full and accurate records of their business. These core obligations under PRA remain as important as ever. The government response to COVID-19 is driven by information and data, which need to be sustained and accessible through effective IM. We rely on full and accurate records to demonstrate accountability.

Compliance trends in 2020/21

In 2020/21 we followed up on almost double the number of incidents (37, compared to 22 in 2019/20). We find out about potential non-compliance issues through various sources:

Our monitoring of regulated parties

Our daily interactions with regulated parties

Complaints from affected or concerned members of the public

Information reported in the media or received from journalists

Complaints from concerned third-party organisations

Referrals from the Office of the Ombudsman.

The Government Loan Service allows the temporary return of public archives to controlling public offices or their successors when required for administrative use, as per section 24 of PRA. In 2020/21 we followed up on organisations failing to meet the conditions of the Government Loan agreement.

The breaches included loss of an archive and the on-loaning of archives to staff not covered in the Government Loan agreement. While these incidents were not of malicious intent, failure to comply with the conditions of Government Loan Service agreement places high-risk and/or high-value records at risk. As a result, organisations had their access reduced or suspended for a three-month period and paid the financial penalty provided for in the government loan conditions.

Compliance in numbers

Visual snapshot of compliance activities for 2020/21; case data current as of August 2021.

37

Incidents required assessment against the PRA.

29

assessments closed with satisfactory assurances or required remediation issues raised

Of the 37, 5

require ongoing remediation or support following resolution of the initial issue

8

continuing at the time of this report

Case study - Office of the Privacy Commissioner Request for assessment

A private citizen contacted us, raising concerns that the Office of the Privacy Commissioner (OPC) was not keeping full and accurate records.

The issue

the Office of the Ombudsman advised the complainant that Archives may be able to address recordkeeping concerns that were related to their OIA complaint. The complainant had requested an exact number of “total contacts” between the OPC and a law firm who the OPC conducted business with. The complainant believed the total number of contacts would be far more extensive than the figure that they received in the OIA response from the OPC. The complainant referenced Section 17(2) of the PRA, noting that “a public office must maintain this information in ‘an accessible form, so as to be able to be used for subsequent reference’.”

Outcome

Archives contacted the OPC for clarification regarding emails described in the complaint, that were kept in accordance with section 17 of the PRA. We acknowledged the role of the Privacy Act 1993 to protect confidentiality of the complaints process (as the case occurred before the enactment of the Privacy Act 2020). The OPC responded by referring to its recordkeeping policy and procedures, noting that a date queried had been corrected in the summary that was released to the complainant. Another check of their recordkeeping system identified one additional contact between the OPC and the law firm used (on a different and unrelated matter). The OPC updated the complainant for their reference. This is a good example of how an organisation can use and rely on their investment in IM. The OPC was able to provide clarity and assurance to the public that it is meeting its legislative obligations and upholding transparency within the framework of its privacy responsibilities.

Case study - Department of Corrections

Request for assessment

Radio New Zealand (RNZ) published an article online titled “Prolonged confinement of prisoners could prompt legal action against Corrections”. The Chief Archivist noted that recordkeeping issues were mentioned in the article and tasked Archives to follow up on those matters.

The issue

RNZ reported inmates at the Auckland Regional Womens Correctional Facility (ARWCF) had been denied the minimum one hour out of their cells each day that is required under the Corrections Act 2004. The Department of Corrections acknowledged in the article that they did not have adequate records to check how many times this had happened. Archives asked Corrections about what failures in information management processes had been identified and, as a result, what policy or procedural changes had occurred in response. Corrections’ response cited the impact that COVID-19 had had on people in prison and staff. Temporary measures, such as keeping prisoners in their cells, were put in place to stop the potential spread of the virus. Corrections argued that the safety of the prisoners was the top priority but conceded that COVID-19 had led to a weakening of recordkeeping practices as additional pressure was placed on staff.

Outcome

Corrections had initiated an Operational Review of the situation at ARWCF prior to being contacted by Archives, which addressed the recordkeeping concerns. Corrections also tasked the new ARWCF Prison Director with implementing and tracking recommended improvements. In response, Archives recorded the case as closed. This case demonstrates how recordkeeping is a fundamental requirement of effective operations. Tracking and recording the routines and movements of people in prison in fundamental to ensuring that their statutory entitlements are met in accordance with legislation. These records take on greater importance, not less, when there is a heightened risk of person-to-person spread of disease.

Case study - Following media leads

Archives monitors the media for information management issues. By focusing on issues raised by the media, Archives seeks to ensure public confidence that the regulator is acting on their behalf in addressing the issues. These are often reported in terms of the harm done, a privacy breach for example, but the underlying cause is often deficiencies in information management practice.

Victoria University of Wellington

Archives noted a news story on the Stuff website which reported that Victoria University of Wellington had accidentally deleted all the files stored on the desktops of staff and student computers. The university said it happened following routine maintenance to clear disk space. We asked Victoria University of Wellington if any of the data loss affected public records in their care. The PRA states that a public record means a record or class of records, in any form, in whole or in part, created and received by a public office in the conduct of its affairs. This definition does not include records created by academic staff or students of a tertiary education institution, unless the records have become part of the records of that institution. Victoria University of Wellington said there was no evidence of any public records being deleted. Unused user profiles are routinely removed from the university devices to free up space. A change to how the tool reads modified dates meant some current profiles on devices were deleted.

Information loss was limited to profile information that included browser bookmarks and images. The way the tool works had changed due to recent Microsoft updates. The university was investigating other options to carry out their maintenance work. Staff and students were reminded that saving data on local drives and user folders may result in loss if this information is not backed up to approved university systems. The university’s full response to our inquiry showed that the initial media report had significantly overstated the nature and seriousness of the incident. While media reports sometimes don’t present the full complexity of information management, they do indicate an awareness of its importance to enabling accountability. This case is still a good reminder as to why important information should be backed up to an appropriate system and of the risks associated with updates and shared network drive use.

Annual Survey

In 2020/21 Archives New Zealand conducted its third annual survey of information management (IM) practices in public offices and local authorities. When we reinstated the survey in 2018/19, we selected a handful of indicators to measure the overall state of public sector IM. The indicators provide a high-level perspective on whether IM is improving, declining or remaining stable. They focus on:

Implementing governance groups for IM

Overall number of IM staff employed by public sector organisations

Identifying high-value and/or high-risk information

Building IM requirements into new business systems

Active, authorised destruction of information

The key indicators are not the sole measure of the state of public sector IM, but we consider them to be fundamental building blocks for effective IM. As with past years the 2020/21 results will be reported in a separate findings report and we will publish the raw data on data.govt.nz.

Some key indicator responses call for action. Because of the responses received to indicator 4. Building IM requirements into new business systems, we presented to the Public Sector CIO Forum on the importance of IM by-design. We intend to engage with Executive Sponsors and the sector on this topic.

Archives continues to work with both IM professionals and Microsoft to ensure that public organisations adopt Microsoft 365 – the main content creation environment used across government – in a way that delivers the requirements of the standard and the PRA.

The survey was sent to 258 public sector organisations. Executive Sponsors from organisations in scope were asked to coordinate their organisation’s response. The survey recorded an 84% response rate, slightly up on last year’s figure of 80%. Public offices are required to respond by direction to report (section 31, PRA). The following table is a list of non-respondents to this year’s survey. The full Findings Report – Survey of public sector information management 2020/21 will provide the complete list of respondents. Keep an eye out for its release in February 2022.

List of non-respondents (A-Z)

Organisation name | Response |

|---|---|

AgResearch Limited | No response |

AsureQuality Limited | No response |

Buller District Council | No response |

Callaghan Innovation | No response |

Carterton District Council | No response |

Chatham Islands Council | No response |

Department of Conservation | No response |

Gore District Council | No response |

Hastings District Council | No response |

Health Quality and Safety Commission | No response |

Hurunui District Council | No response |

Hutt City Council | No response |

Invercargill City Council | No response |

Judicial Conduct Commissioner | No response |

Kaikōura District Council | No response |

Kawerau District Council | No response |

Marlborough District Council | No response |

National Pacific Radio Trust | No response |

New Zealand Parole Board | No response |

New Zealand Symphony Orchestra | No response |

New Zealand Walking Access Commission | No response |

Opotiki District Council | No response |

Otorohanga District Council | No response |

Palmerston North City Council | No response |

Retirement Commissioner | No response |

Rotorua Lakes Council | No response |

Serious Fraud Office | No response |

South Canterbury District Health Board | No response |

Taranaki Regional Council | No response |

Te Wānanga o Raukawa | No response |

Television New Zealand Limited | No response |

Waipa District Council | No response |

West Coast Regional Council | No response |

Update on the Royal Commission of Inquiry Into Historic Abuse

Listening, learning and changing

In 2020/21 the pace of the work of the Royal Commission of Inquiry into Historic Abuse increased significantly, with six hearings. As part of the Crown Response, Archives continued to support the Royal Commission by providing the large volumes of information requested, either via digital copies (to reduce the risk of damage or loss of records that are of interest to the Commission) or by access to our reading room. As a regulator, we have also continued to provide advice to agencies and the Royal Commission on government records management, including support relating to the disposal moratorium.

The testimony of abuse survivors has shone a light on the harm experienced by large numbers of children, young people and vulnerable adults in care between 1950 and 1999, and beyond. Many have shared their stories to ensure the same things do not happen in the future.

Archives, in our work supporting the Royal Commission, is listening and learning from what is said. Our involvement has highlighted the importance of the current regulatory framework for public sector information management. The evidence presented this year to the Commissioners has shown the real human impacts of recordkeeping practices and decision-making. It has demonstrated the importance of creating and maintaining full and accurate records in accessible form and of authorised disposal. Government recordkeeping has been criticised in public hearings and the Commission’s interim report. We anticipate that these concerns may continue to feature in the work of the Commission.

This year we worked with the Crown Response’s multiple agencies and the Royal Commission to improve options for the Commission to access information at Archives when using its powers under section 20 of the Inquiries Act 2013. This means the Royal Commission’s investigation teams can determine if particular restricted archives held by Archives are relevant and can gain the information required more efficiently.

Redress is a key element of the Royal Commission’s interests, and the various hearings throughout 2020/21 have raised opportunities for our regulatory work. Several of these are already progressing through existing Archives work on improving the appraisal and disposal framework, descriptive metadata (including Māori metadata) and access status information. All relate to the themes of disposal, access and Te Tiriti o Waitangi and their relevance to redress. The evidence in records can help individuals who seek redress for abuse while in care. This means decisions around retention and disposal of records and access to records can have considerable and far- reaching consequences.

Ongoing disposal moratorium

In 2019 the Chief Archivist issued a general notice putting in place a moratorium on the disposal of records held by all public offices which may be relevant to the Royal Commission’s inquiry. The moratorium has no fixed end date and will remain in place until the Chief Archivist determines it is no longer required.

Since then the Royal Commission has built up a clearer picture of the type of information they are seeking. To reflect this, Archives issued an update and a reminder that the moratorium remains in effect. We sent information to all public office Executive Sponsors to circulate around their organisations, and we posted an update on our website.

We drafted the update in consultation with the Royal Commission’s information management team. It restated the original purpose of the moratorium, set out frequently asked questions and updated how public office queries were to be handled. This reflected the more direct role the Royal Commission was taking in determining what records were relevant to their investigations and whether the disposal would interfere with the conduct of the inquiry.

Two other major issues have arisen since the moratorium was issued: how to apply the moratorium to the destruction of digitised source information, and the Royal Commission’s determination that all DHB records are relevant to their inquiries.

Under the Contract and Commercial Law Act 2017 and the PRA, public offices and local authorities can destroy source information that has been digitised as long as the prescribed digitisation standard and a set of selection criteria have been met. But in light of the moratorium and the work of the Royal Commission, all agencies are being advised that they need to seek the endorsement of the Royal Commission before proceeding with any destruction under these provisions. This is to ensure that the Royal Commission is satisfied that the digitisation processes and systems being proposed are sufficient to ensure that the integrity of the information is not compromised, and that any records which may have an intrinsic for the inquiry are preserved.

Archives continues to support the Royal Commission and its inquiry, as well as agencies responding to it. In October 2020 we engaged with all DHB Information Management Executive Sponsors to help them understand how their role could support the work of the Inquiry. This included control of and access to information, outsourced business, and the disposal moratorium.

In 2020 the Ministry of Justice advised us that it had disposed of 5,500 legal aid files without first confirming that they were not relevant to the Royal Commission. The Ministry’s internal investigation found that these records did not appear to be related to historic abuse claims. Nonetheless the Ministry moved swiftly to ensure there is no future disposal of records potentially related to the Royal Commission. It implemented training for records advisory staff, updated its disposal guidance and knowledge bases, and informed and reminded all staff about the moratorium.

Projects and initiatives

Highlights 2020/21: an overview of our ongoing work

Appraisal, disposal and implementation redesign project

Appraisal and disposal are essential to good information management and governance practices. Together they help define every major decision involving the management of a record.

It remains difficult for many government agencies to manage their appraisal and disposal processes efficiently, particularly in the digital age. This can be due to low levels of maturity of recordkeeping, and issues with the IM practices of many public offices. The rapid adoption of digital technologies has seen explosive growth in digital information created by government. Despite this, many agencies do not have the appropriate processes needed for good recordkeeping built into their systems. There is also a low acceptance of information as a key strategic asset, and low levels of digital disposal.

Archives New Zealand’s Appraisal, Disposal and Implementation (ADI) redesign project aims to design an overhaul of the components of our regulatory system that support robust appraisal and disposal processes. It recognises the need to transform Archives’ approach into a fit-for purpose, digitally focused service, as well as change how the entire sector manages its records in the coming decades.

This is in keeping with the IM goals of the Archives 2057 Strategy – upholding transparency and building systems together. The ADI redesign project is about helping and requiring agencies to manage information according to its value from point of creation. It will also explore ways to ensure that Māori perspectives on the significance and value of information are part of an agency’s appraisal and disposal decisions.

The ADI redesign project is likely to be a multi-year programme with three stages: the current discovery phase, followed by a design phase and a delivery phase. It involves Archives and the sector, and takes an all-of-government approach. The discovery phase will re-examine and test the known issues and opportunities for improvement, and propose a programme of work.

All-of-Government ontology

Hundreds of different agencies collect data across New Zealand’s public sector. Each one creates records for different purposes, stores them in various formats, and uses different categorisations. This means information from other organisations can be hard to access. A ‘cow’ at the Ministry for Primary Industries, for example, is ‘cattle’ at Inland Revenue and ‘Bos taurus’ at the Department of Conservation. Changes in agencies over time make the challenge even greater: the Royal Commission’s Abuse in Care Inquiry shows how challenging it can be for individuals to find their information when agencies have merged, changed function or rebranded.

A common language that supports government recordkeeping is needed – and modern technology and techniques can help. An all-of-government ontology would support both agencies and New Zealanders to find, use, manage and share their information and data. An ontology is a framework, that identifies links between different terms and concepts and creates relationships between ideas. This makes data much easier to find. Huge knowledge organisations such as Google and Microsoft use ontologies.

An all-of-government ontology will speed up the move to full digital management of government record-keeping. It meets the key aims of Archives’ 2057 Strategy: upholding transparency, taking archives to the people and building systems together. It also aligns with the Chief Archivist’s primary statutory role through the PRA, to lead public sector information and records management.

A human can quickly contextualise meaning from context, when talking about aircraft we can deduce ‘bank’ means a movement, when talking about budgets, a ‘bank’ is a financial institution, or in geography, a ‘bank’ is a grassy slope. Machines need to be taught these concepts to return information in context.

In 2020/21 Archives explored the benefits of an all-of-government ontology. The result of this work is the All-of-Government Ontology Options Paper, publicly released in September 2021.

Ontologies analyse and auto-categorise content through linguistic meaning to improve access. They support the automation of business processes, and the use of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine-learning tools. These tools represent the future of information management.

Archives consulted across sectors, talking to 75 representatives from central government, local authorities, academia and the private sector. Interviewees were enthusiastic about this innovative opportunity. They believe it would move Archives New Zealand forward in its aims, and also provide huge benefit across government.

An all-of-government ontology will allow consistent categorisation of government information. This will improve access to holdings from many points of view, both cultural and multilingual, including Te Ao Māori and te reo Māori. It could support data sharing, automatic categorisation and classification of content and data analytics.

Archives is working with partners with a mutual interest in establishing an all-of-government ontology. We also plan to look at working with a major cloud service provider. This would help integrate an all-of-government ontology into advanced artificial intelligence tools. The Options Paper supports alignment with Digital Public Service initiatives, in particular the Digital Public Service Strategy (Department of Internal Affairs, 2020).

An all-of-government ontology would help organisations create an automated digital disposal schedule. Government departments have a legal responsibility to delete, transfer or archive records according to agreed retention and disposal schedules. But as volumes of information increase so do the challenges of identifying and sentencing digital records on time. The ever- growing digital stockpile of information is too overwhelming for people to manage. Auto- classification is now the only viable solution to manage information and understand regulatory requirements.

Information management maturity assessment

The Information Management Maturity Assessment provides a consistent framework for the PRA audits of public offices that started in late 2020. It is based on the requirements of the PRA and the Information and records management standard. It is also available online, so that public offices and local authorities can self-assess their own IM maturity at any time.

The IM Maturity Assessment provides clear and specific guidance on Archives’ expectations for IM maturity within public offices and local authorities. An organisation that is at the ‘Managing’ level of maturity is broadly meeting the minimum requirements expected by the PRA and the Standard.

We developed our maturity model after extensive consultation with the sector during the development phase. An external reference group comprising 10 IM staff from a wide range of public sector organisations provided constructive feedback on the draft model. We know our regulated parties use many maturity frameworks and, while useful and relevant, they all have a compliance cost. We have therefore worked hard to ensure there was no unnecessary duplication in creating our model.

For Archives, the next steps are how both we and the IM sector can make further use of the IM Maturity Assessment.

Standards

The mandatory Information and records management standard has been in place since 2016. The current audit programme is built around the minimum requirements contained within this standard. It is now timely to review Archives NZ standards approach.

The provision of more detailed direction and clear expectations has been raised by regulated parties in both our annual surveys and in some audit responses. This need for clear direction will become more important as we redesign and roll-out the revised appraisal and disposal regime. Solution for managing digital recordkeeping and maintaining access to digital records over time will also likely require mandated prescriptive requirements. The development and promulgation of a standard will not in itself ensure compliance. An integral part of this work will be ensuring there is a supporting monitoring regime.

Sector snapshot: Accident Compensation Corporation and the Workplace Wizard

Organisations must build information and records management into their systems and service environments. This is particularly important where the business involved is high-risk, high-value, or both. At ACC, staff use a specialised information management tool, the Workspace Wizard. It uses Microsoft 365 tools and development frameworks to create digital workspaces and manages ACC’s corporate content and its intranet in one place. ACC schedules appropriate retention periods using File Plan, Microsoft 365’s record keeping software. Currently, ACC takes a bulk approach to managing and storing its records within the organisation. But in future, it plans to refine classification processes and introduce automated disposal methods. As part of this, ACC is updating its Disposal Authorities to suit the modern world, making records identification simpler and understandable using machine logic.

Microsoft 365 boasts “Swiss Army knife capabilities that you can personalise for your own organisation’s IM”, says ACC Manager for Information Management Paul O’Donoghue.

But ACC had to rethink its original design for its digital workspace. “At first we thought about records management as a formal structure to contain and control information. Then we moved to thinking of information as having a life cycle, which you manage from its creation to its end, while empowering your staff to have the flexibility in how they utilize the tools. It’s about being able to find information, access it, leverage it and use it for the future.”

Sector snapshot: Tararua District Council

Post-launch feedback suggests IM professionals can, as we intended, use the IM Maturity Assessment to carry out improvements in IM practice in their organisations. At the Tararua District Council (TDC), the tool has been “invaluable” in helping TDC drive its new IM Strategy says the TDC’s Records & Information Manager.

The Records & information Manager was part of the external reference group which provided feedback on the draft version of the IM Maturity Assessment tool. The tool was used to prepare an assessment of TDC’s IM maturity levels, which was submitted to the TDC’s new Chief Executive (CE) and Executive Sponsor (ES) for IM.

The Records & information Manager noted: “It was the ideal method to bring our new CE/ES up to speed on the status of IM within our organisation. The TDC’s new CE was very impressed with the clarity the tool offered. TDC have now adapted the tool to include a risk assessment based on where we are at and what needs to happen in order to move forward.”

TDC also has an IM Governance Group which meets quarterly to discuss such issues. “The tool has been invaluable to us. It means our organisation can easily identify what needs to be done to progress to each level. I can also cite appropriate categories to be met in relation to future project proposals.”

Improvements to our website

This year we launched a series of improvements to the Archives website. This phase, completed in May 2021, focused on the Manage Information section of the website. We wanted to make sure that information management (IM) professionals could find the content they need to do their jobs and comply with PRA. Another goal was to improve the user experience, to make information gathering less time-consuming for both IM professionals.

User feedback and a 2019 survey showed that it wasn’t always easy to locate information. A second survey, of 218 users in November 2020 confirmed this, while user testing showed us what changes we needed to make. We improved the way content was organised, and created new navigation pages to make it clearer where pages are located. We also produced an A to Z list of information guides to make them much easier to find. Small tweaks to the design and page layout also make the website more user-friendly.

Feedback from the IM sector has been positive, while recent analytics since the changes have shown a marked increase in engagement. Archives will continue to improve its website for IM users. The web team will use the 2019 and 2020 surveys as a benchmark, to see where we can make future improvements. We are also working on replacing our online finding aid Archway, which we expect to launch in 2022. This upgrade will provide easier access to government information.

Microsoft 365

Digital technology drives the way government agencies work and how we create, manage, access and store records. But the principles of record-keeping have not changed. We must create and maintain the records of government regardless of the method of data creation. In our 2019/20 report we noted how Archives is working with both IM professionals and Microsoft to ensure that Microsoft 365 – the main content creation environment used across government agencies – complies with the Standard and the PRA.

Microsoft 365 is only compliant with the Standard or the PRA when it is appropriately configured and integrated. Archives NZ provides guidance on how organisations can move toward compliance by applying controls, managing disposal and identifying risks. Retention and disposal are particular concerns for the sector. This year, we have begun looking at how to help agencies deal with these. We are also working with Microsoft as well as the Council of Australasian Archives and Records Authorities (CAARA) to ensure we take the perspectives of wider government and similar jurisdictions into account.

Digital aspirations

The 2019/20 survey of Public Sector Information Management identified a number of risks and costs resulting from the following key digital capability issues:

data deterioration and inaccessibility, especially of older digital information formats

inability to identify information that may relate to Māori

inability to identify and classify information accurately (often resulting in no access and both over- and under-retention)

lack of dedicated and qualified information management staff and capability for digital records management.

These capability and capacity deficits undermine public trust in Government and democratic transparency and fail to meet Te Tiriti partnership responsibilities.

Māori and iwi have told us that they cannot currently easily find or access their taonga. It is crucial that we work towards a future where Māori know what recorded taonga, documentary heritage and mātauranga Māori exists, what is held by the government, and that Māori can access taonga in a way that suits them best.

As a regulator, Archives has a relationship with all of government that needs to be redefined to meet the changing needs of the digital world now and into the future. We need to move to a state where our information is preserved, securely managed and maintained, ensuring timely and enduring access. We must work on systems and information architecture, and the skills and capabilities of our kaimahi, our processes and our tools so that we can scale as required and meet our collection needs.

The National Library and Archives are working together with Ngā Taonga Sound & Vision to support and enable access to mātauranga Māori through improvements in digital capability. We are committed to upholding te Tiriti o Waitangi, and plan to do this by working with Māori to enable hapū and iwi to access and manage mātauranga Māori held by the government.

The three institutions are working on a programme that will enable more New Zealanders to discover, access and use Aotearoa’s documentary and recorded heritage and government information anywhere, anytime. This will reduce current inequities in access and improve user experience.

The programme will support more effective ways of working together, while increasing the value provided to the public through education and access to knowledge. It will also deliver the digital experiences for Tāhuhu, the programme overseeing the construction of modern, purpose-built facilities that will preserve New Zealand’s documentary heritage.

Understanding the Public Records Act 2005 and the role of Archives New Zealand Te Rua Mahara o te Kāwanatanga

What the Act does

Records of public sector activities have always been kept. However, until the introduction of PRA, there was no general legislative requirements for what information and records needed to be created and managed.

The PRA sets out the regulatory framework for information management across the public sector. The primary purpose of the PRA is to enable the accountability and transparency of government decision making by ensuring organisations create and maintain full and accurate records of their activities.

The PRA also establishes the statutory role and duties of the Chief Archivist. These include:

exercising a leadership role of information management across public offices

setting standards for public sector information management

authorising the disposal of records when they are no longer required for business purposes

providing advice and support for organisations so they can comply with the requirements of the PRA.

Who the Act applies to

Public offices and local authorities are covered by the PRA, although with different compliance requirements. A wide range of organisations are public offices, including government departments, district health boards, Crown entities, state owned enterprises, school boards of trustees and government ministers.

Regional councils and territorial authorities are local authorities under the PRA. Council-controlled organisations, council-controlled trading organisations and local government organisations are also considered local authorities under the PRA.

How we regulate

The PRA establishes the Chief Archivist as an independent information regulator within government. In delivering this role, the Chief Archivist and Archives New Zealand have responsibility for supporting, monitoring and directing the public sector to facilitate compliance with information management requirements. These requirements are set out in the Standard.

We regulate approximately 3,000 public offices and local authorities, which includes 2,500 school boards of trustees. These organisations vary widely in their size, complexity, access to funding, staffing levels, and the number of functions they carry out.

These factors all affect the level of information management maturity in organisations, as well as the level of risk associated with not being able to find or access information that has been created.

Archives monitors change in the structure of the public sector and relevant legislation to ensure that both Archives and regulated parties correctly understand the extent of our regulatory responsibilities.

There are two instances where an organisation can be defined as a public office by legislation:

if an organisation is defined as a public office in section 4 of the PRA

if an organisation is otherwise defined as such in other legislation.

The types of organisations are that defined as public offices under the PRA include:

all departments as defined in section 5 of the Public Service Act 2020 including departmental agencies and interdepartmental executive boards

interdepartmental ventures as defined in section 5 of the Public Service Act 2020

all Offices of Parliament as defined in section 2(1) of the Public Finance Act 1989

all state enterprises as defined in section 2 of the State-Owned Enterprises Act 1986

all Crown entities as listed in Schedule 1 and Schedule 2 of the Crown Entities Act 2004 including:

Crown agents

autonomous Crown entities

independent Crown entities

Crown entity companies

All Crown entities as defined in section 7(1) of the Crown Entities Act 2004 including for example:

boards of trustees for state and state integrated schools

tertiary education institutions including colleges of education, polytechnics, specialist colleges, universities, and wānanga

Crown entity subsidiaries (dependent on control factors).

Glossary of terms

Public record

Means a record or class of records, in any form, in whole or in part, created or received by a public office in the conduct of its affairs. This includes estray records.

The Standard

The Information and records management standard (16/S1) issued by the Chief Archivist.

Disposal

The range of activities, defined in PRA, that can be applied to public and local authority records that are no longer of active business value. This covers transfer of control; sale; alteration; destruction; or discharging of records.

Local Authority

Regional council or territorial authority, including:

a council-controlled organisation

a council-controlled trading organisation

a local government organisation.

Public Sector Organisation/Regulated Party

Umbrella term used by Te Rua Mahara Archives New Zealand to describe all organisations subject to the Public Records Act 2005, including public office and local authorities.

RK Advice Service

A phone and email advisory service for all government and local authorities seeking advice or assistance with information management (IM) matters.